TRANSFORMING LITERACY ASSSESSMENT PRACTICES

THROUGH AN ACTION RESEARCH PROFESSIONAL

LEARNING COMMUNITY

Arlene L. Grierson and Vera E. Woloshyn

Brock University

Abstract

Researchers and educators acknowledge that early reading instruction is of critical importance, with interventions and remedial programming most effective in the primary grades. Integral to this programming are educators' abilities to assess students' reading strengths and needs, with inconsistent and/or inaccurate practices ultimately threatening students' learning potential. This two-year project explored the effects of teachers' participation in an action research professional learning community, focused on the development and use of primary-grade cumulative literacy assessment portfolios, in an attempt to streamline assessment practices and facilitate implementation of responsive early reading programming.

Introduction

Professional learning communities are exemplified by collaborative reflective exploration of issues and problems with the intent of generating strategies that will bring about positive change (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2005). One significant issue confronting teachers is how to maximize students' growth in reading during the primary grades as these years have been identified as a critical period for learning to read (National Reading Panel, 2000; Ontario Ministry of Education, 2003; Snow, Burns, & Griffin, 1998). It has been shown that teachers' abilities to provide effective primary grade reading instruction are related directly to their abilities to collect, analyze and interpret classroom-based assessment data (Invernizzi, Landrum, Howell & Warley, 2005; Paris & Hoffman, 2004). In addition, the importance of cross-grade collaboration in enhancing students' potential for reading success has been highlighted (Earl, 2003; Snow et al., 1998), with cumulative profiles of students' assessment data being recognized as an effective tool for this purpose (Partridge, Invernizzi, Meier, & Sullivan, 2003; Walpole, Justice & Invernizzi, 2004).

Before teachers can engage in collaborative use of assessment data, however, they need to possess sound classroom-based assessment competencies (Black & Wiliam, 1998; Earl, 2003; Paris & Hoffman, 2004; Partridge et al., 2003), with the acquisition of these skills often dependent upon long-term, assessment-focused professional development (e.g., Black & Wiliam, 1998; Paris & Hoffman, 2004). Teacher action research groups have been identified as one type of professional learning community that has the potential to provide the support required to facilitate sustainable change in teachers' classroom-based assessment practices (Black & Wiliam, 1998; Hensen, 2001; Stringer, 2004).

The purpose of this paper is to describe a two-year project that explored primary-grade teachers' participation in an action research professional learning community focused on the development and implementation of cumulative classroom-based literacy assessment portfolios. We were especially interested in answering the research question, how does participation in a professional learning community engaged in action research affect primary-grade teachers' literacy assessment and instruction practices? We were also interested in exploring how teachers' understandings of assessment competencies and collaboration developed throughout the duration of this study.

Methodology

Context and Participants

This study took place over a two-year period at a moderate-sized Ontario school board servicing predominately European-Canadian students. Eighteen educators from three diverse school settings were invited to participate in an action research project that followed the action research cycle and process described by Sagor (1992) and Kemmis (1983). Brenda, Dianna, Sandra, Kathy, Glenna, and Randy (pseudonyms) were from an urban area school serving primarily students of below-average cognitive abilities (as determined by Canadian Cognitive Abilities Test scores). Janet, Krista, Carol, Joanne, Nicole, Verna and Tom (pseudonyms) were from a rural-suburban area school, serving largely students of average cognitive abilities. Kim, Judy, Linda, Holly, and April (pseudonyms) were from a rural-suburban area school, serving predominately students of above-average cognitive abilities. Participants included primary-grade classroom teachers and the special education resource teacher from each school site, and one administrator. While the role of the primary-grade teacher participants was to develop, implement, and evaluate research-based assessment and instructional practices in their classrooms, the role of the special education resource teachers was to provide additional support to students and their teachers in this process, in an attempt to increase programming consistency and ultimately, student achievement throughout the primary grades. The role of the administrator was to provide administrative insights and support. Teaching experience of these participants ranged from less than one year to in excess of twenty years. The action research group also included a school-board literacy support teacher who was the facilitator and primary researcher. During the two-year study, the school district provided eight days of release time per participant.

Two years prior to the commencement of this study, all teachers participated in an early literacy board-wide professional development program. Despite this programming however, all teachers in this study had expressed uncertainty about their literacy assessment practices, especially with respect to tracking the cumulative progress of students' skills. Lack of consistent practices required teachers to recreate baseline assessment data, often using diverse assessment tools, on a yearly basis. These inconsistent data sources provided little insight to the special education resource teachers, who, in turn, were often required to administer independent assessments. Consequently, these teachers found it difficult to maximize instructional time and student learning potential.

Procedure

Phase One - The first phase of this study occurred across two days at the end of a school year, and one day at the outset of the subsequent school year. During this phase, participants used information gathered from the literature (e.g., Johns, Lenski, & Elish-Piper, 1999; National Reading Panel, 2000), the provincial curricula, and their collective experiences, to determine grade-specific literacy skills for assessment and to select data collection tools. Over time, the participants elected to assess the following skills: print concepts, phonemic awareness, letter-sound identification, high frequency word identification, reading fluency, reading comprehension, and encoding/spelling.

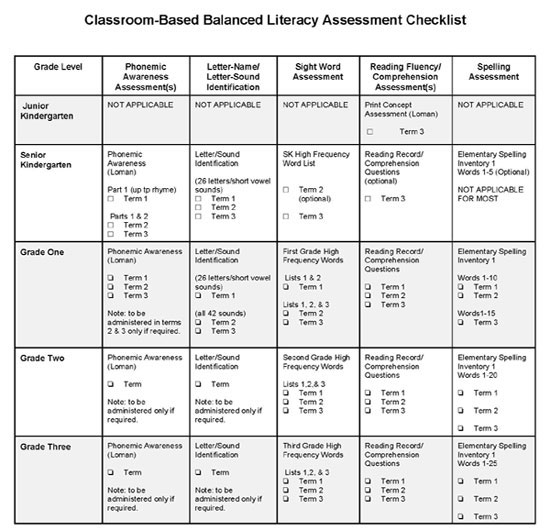

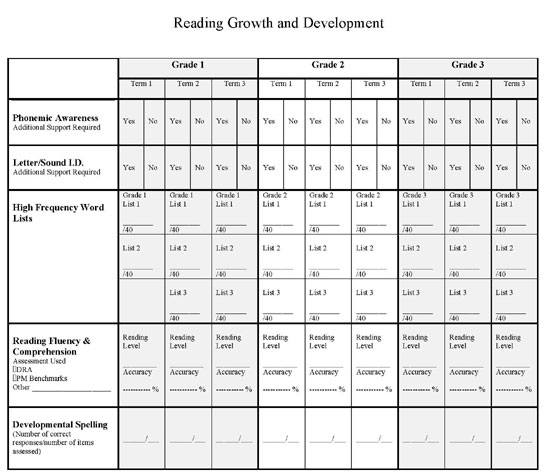

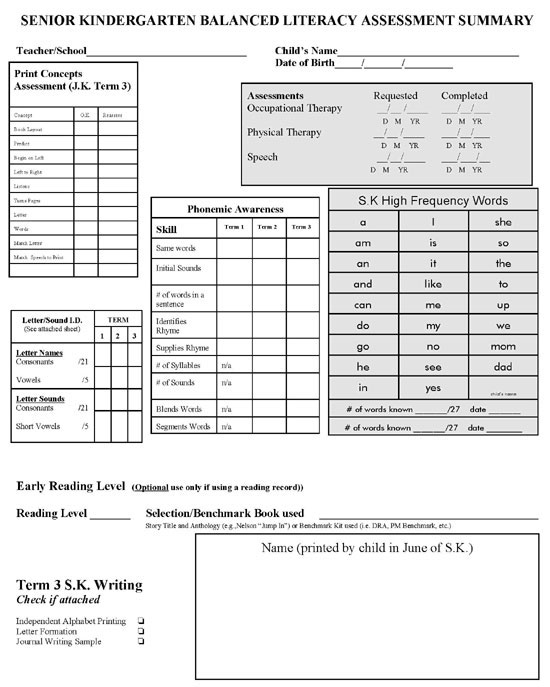

Participants then discussed their current assessment practices (i.e., tools and schedules), and negotiated a set of criteria (e.g., teacher familiarity, user-friendly protocols) by which to select assessment tools. Participants outlined the need for manageable assessments with clear assessment protocols that would delineate the focus for classroom literacy instruction. In the case of letter-sound and high frequency word identification skills, the group concluded that there were no suitable commercial products available that reflected district programming requirements. Accordingly, they decided to develop and use "in-house" assessment tools. Table 1 outlines the classroom-based literacy assessment instruments selected for each identified skill. Assessment protocols were reviewed and clarified for commercial tools used (e.g., informal reading inventories) and established for tools developed by the action research group (i.e., letter-sound identification, sight word lists). While reviewing the assessment guidelines, participants identified the need for additional professional development to enhance their abilities to administer informal reading inventories. Professional development was provided subsequently. Additionally, a grade-by-grade, term-by-term assessment administration schedule (Figure 1) was developed. Working in same-grade groups, teachers identified implementation challenges (e.g., time, support), and strategies (e.g., assistance from parent volunteers, optimum times to conduct assessments) that could be used to overcome them. Summary tracking sheets (Figures 2 and 3) were developed to create an, "at a glance" profile of students' skill development. Finally, p articipants developed a set of "rules" that would govern the cumulative portfolio to avoid duplication of assessment. For instance, once print concepts, phonemic awareness, and letter-sound identification skills were identified as "developed", they would not be reassessed. Conversely, if these skills were not mastered in any one year of the primary grades, they would be reassessed the following year. Grade specific high frequency word identification, reading fluency, reading comprehension, and spelling, would be assessed once per term throughout grades one to three.

Participants then made decisions about data collection methods. They chose to complete a common survey documenting their experiences administering each of the assessment tools each term. Additionally, participants determined that they would independently review each other's student assessment portfolios in order to create profiles of these students' reading strengths and needs. These profiles would later be discussed with the teachers who conducted the assessments.

Phase Two - During the second phase of the study, teachers field-tested the assessment tools following the grade-by-grade, term-by-term, administration schedule they had developed in Phase One. They also completed surveys about their assessment experiences documenting implementation challenges and recommendations for improvement. These completed surveys and student portfolios provided the focus for the full-day research meetings held at the end of each of the three school terms, during the first year of the study. In addition to reviewing the survey responses, all participants independently reviewed five portfolios created by teacher-participants at the other two schools. As well as reviewing the portfolios for completeness, teachers used the portfolios to create profiles of students' reading strengths and needs, and develop recommendations for programming. The profiles were later reviewed and discussed with the teachers who conducted the assessments, with special attention provided to how enclosures delineated instructional priorities and how the portfolio summary tracking and individual assessment recording sheets could be enhanced for subsequent use.

Collectively, the action research sessions provided opportunities for participants to analyze the effectiveness of the portfolios, share implementation challenges, and revise the assessment tools, tracking sheets, and administration schedules. Additionally, students' grade-by-grade and skill-by-skill results provided a springboard for discussions about effective related instructional strategies. Over time, participants expressed the need for the inclusion of criterion-referenced assessments with individual and class profiles that could denote specific skills for instructional focus, resulting in revision of the selected phonemic awareness and encoding assessment tools (Table 1).

Phase Three - During the third phase of the study, participants continued to use and evaluate the effectiveness of the portfolios. Meetings were held once in the fall and once in the spring of the second year, at which time participants continued to explore the benefits and challenges of portfolio implementation. For example, teachers acknowledged that having access to the portfolios in September enabled them to begin programming for students immediately as they did not need to gather baseline assessment data. They also discussed challenges they encountered in using the individual student assessment tracking sheets (e.g., omission of marking templates) and cumulative profile sheets (e.g., omission of decoding accuracy rate) and suggested modifications to these tracking tools. Participants also reviewed an administration guide prepared to assist teachers with portfolio implementation and drafted recommendations for other schools interested in implementing assessment portfolios.

Data Collection and Analysis

Multiple sources of evidence including field notes, interviews, surveys, and artifacts were collected in all three phases of this study. In keeping with the dynamic nature of action research, artifacts (e.g., revised assessment schedule, tracking sheets) were added and reviewed as they became relevant to the study (Stringer, 2004). Data analysis consisted of coding and categorizing as described by Creswell (2002, 1998). Field notes, interviews, teacher surveys, action- research group meeting minutes, and reports were reviewed for recurring themes that provided insights with respect to how participation in an action research professional learning community affected primary-grade teachers' literacy assessment and instruction practices. Following this process several themes emerged including: (1) assessment portfolio benefits, (2) teachers' diverse assessment administration preferences and, (3) the on-going teacher support required.

Results & Discussion

Assessment Portfolio Benefits

All participants believed that their assessment practices became more streamlined and that their literacy instructional practices improved as a function of implementing the assessment portfolios. While participants acknowledged difficulties associated with the assessment process (primarily time), they concluded that the generated profiles demonstrated students' reading strengths and needs, and provided valuable insights with respect to large-group, small-group and individual instructional requirements.

I was more analytic. The class profiles delineated instructional priorities. We could see which needs should be addressed by parent volunteers and the LRT [special education resource teacher]. For example, if one or two students had not mastered initial consonants and short vowel sounds, it was not necessary to teach that skill to the entire class but just to those students. When the majority of students had not mastered consonant digraphs or diphthongs, we could focus our lessons on these skills (Nicole).

Classroom teachers commented about their increased abilities to identify children in need of early intervention and remedial programming. "We identified 'at risk' children sooner and had more confidence going to in-school team" (Judy). Teachers' collaboration enhanced implementation of responsive early reading programming throughout the primary grades. "Some students were red-flagged in Kindergarten and grade one and were identified through these assessments, now this [remedial] work can continue" (April).

Special education teachers also attributed increased abilities to deliver responsive reading programming to use of the assessment portfolios.

At-risk students were identified earlier based on a reliable set of criteria and assessment results were helpful for suggesting [remedial] plans to classroom teachers (Randy).

More observant, less panicked teachers resulted in fewer 911 calls, which provided me with more time for those who really need help (Verna).

Additionally, the portfolio data enhanced classroom teachers' abilities to communicate students' progress through report cards and parent-teacher interviews and provided a base from which to provide recommendations to parents.

As the data in our own portfolios accumulated at the end of each term, we were much better prepared to write report card comments that identified specific strengths and weaknesses of our students (Nicole).

This justifies marks to parents and gives a means of explaining the difference between comprehension and decoding to parents (Holly).

When parents asked us what they could do to help their child, we were equipped with the hard data to support the suggestions we made for helping their children both at home and at school (Nicole).

Use of the cumulative portfolios, particularly the student and class summary sheets, eliminated the need to recreate baseline assessment data for new classes in September.

Most importantly, we have a good idea of the strengths and weaknesses of our classes before school begins and will be able to develop appropriate programming and provide the necessary support on the first day of school in September (Krista).

The results were helpful for programming. [you] get a class profile and can immediately find things to focus on - [the tracking sheets] show you weak areas (Kathy).

The tracking sheets are the key (Judy).

The school administrator believed that the portfolios provided teachers with critical information that facilitated their abilities to use clear, definitive comments when writing report cards, as well as, individual education plans. He also believed that the portfolios provided teachers with a common language that could be used during student case conferences and school goal setting.

.from an administrator's point of view, the literacy assessment instrument provides a lot of valuable information. . An interesting anecdote occurred after second term reports when I asked two teachers involved in the creation of the assessment about whether this instrument helped with report card writing. . When it came time to write the report cards they both agreed it made their jobs much easier. They could comment with accuracy where these students were in terms of language development.. Finally, staff's ability to establish school-wide literacy goal setting was enhanced by the availability of baseline literacy data. From a school perspective it assists in planning and developing school improvement plans. As student needs will be reflected, appropriate and attainable targets can be set at both the school and system levels (Tom).

Teachers' Diverse Assessment Administration Preferences

Although all teacher participants followed a common assessment schedule, their unique styles, needs, and interests, were reflected in their assessment administration preferences. For example, while one teacher shared how completing informal reading inventories was, ".almost impossible during class time" (Judy), another experienced the opposite, ".the easiest time to do running records [informal reading inventories] is during an art lesson" (Kathy). Many teacher-participants assessed students during quiet classroom times. "I conducted these assessments during independent work periods such as self-selected reading, computers, art, or centers" (Sandra). As well, participants shared that it was important to assess students in an environment where they would perform at their best, which required some teachers to alter the assessment setting, while other teachers assessed all of their students in their own classroom. "Think about those students that are easiest to distract and need an empty classroom" (Joanne).

Additionally, while some teachers found it effective to have the special education resource teacher conduct some assessments, other teachers preferred to conduct all of the assessments with their own students. This diversity was apparent both between and within school sites. For example, teacher participants reached different conclusions about the value of special education resource teacher assistance administering the phonemic awareness assessment. "This was done by the LRT [special education resource teacher] so I didn't get a good idea of what the results were, next term I'll try to do it on my own"(Diane). Conversely, a same-grade teacher, at the same school, valued the special education teacher's assistance administering the phonemic awareness assessment. "This assessment required a totally quiet room without any background noise therefore I had the LRT conduct the assessment. If you can get LRT assistance with this assessment, it would be helpful" (Sandra). Teacher diversity was apparent whether or not the assessment was one that had been identified by participants as requiring a high degree of skill to administer. For instance, referring to the high frequency word assessment, Holly stated, ".this could be administered by a volunteer, however once again it was [that] I found it helpful to do it myself".

On-Going Support

In reflecting on this study, all participants acknowledged the pivotal role of the school administrator. Janet commented, "Administrators need to bring pressure and support". Participants identified that implementation was most successful when school administrators expected that the assessment schedule would be adhered to, and through "creative scheduling", provided classroom teachers with the time required to conduct the assessments. Recognizing the importance of administrative support, participants suggested that if portfolio implementation professional development sessions were to be offered to other schools, administrators should be required to attend. "These should be 'BYOP' or bring your own principal sessions" (Verna).

While discussing advice they would provide to other schools interested in using literacy assessment portfolios, participants unanimously agreed that although the implementation process was difficult, full implementation (i.e., assessing all skills across all primary grades) was desirable. Should lack of support render this impossible, they concurred that the next best option was implementing the portfolio one grade at a time, beginning with Kindergarten, adding first grade the next year, and so forth. Participants determined that skill-by-skill implementation (i.e., all teachers assessing one skill in the first year, adding additional assessments in the second, and so on) was not a viable alternative as it would provide a limited, rather than complete profile of students' literacy development. "If everyone does phonemic awareness, it doesn't tell you the information you need" (Kim).

Participants acknowledged the value of the professional development provided throughout the action research project. "When this project was started, everyone had training about how to complete running records [informal reading inventories].this is needed" (Kathy). Participants also appreciated the opportunities to share insights and successful strategies with their primary-grade colleagues. "A grade-by-grade perspective is needed as Grade 3 teachers are not totally aware of what happens in Grade 1" (Dianna). Recognizing the value of collaboration participants highlighted that further portfolio implementation plans should include mentoring opportunities. "Teachers need to meet with a school that has worked through the process [and have] time to discuss challenges to implementation" (Dianna).

Concluding Comments

This study demonstrated that participating in a professional learning community engaged in action research can transform teachers' literacy assessment practices. Through the creation and use of cumulative literacy assessment portfolios, the action- research group members streamlined assessment practices, eliminated duplication, and enhanced student learning potential through individualizing literacy instruction. While the participants acknowledged the value of the development of an effective template for the creation of primary-grade literacy assessment portfolios, they also acknowledged the pivotal role of participating in a professional learning community engaged in action research throughout implementation . Ideally, the foundations for reading achievement are established in the primary grades (National Reading Panel, 2000; Ontario Ministry of Education, 2003; Snow et al., 1998). Effective literacy assessment enhances teachers' abilities to provide targeted responsive instruction (Invernizzi et al., 2005; Paris & Hoffman, 2004; Snow et al., 1998). The professional learning community created through the action research study described here, legitimized participants' perspectives and provided them with the support required to change their classroom-based assessment practices (Black & Wiliam, 1998; Earl, 2003; Hensen, 2001). Participants credited their increased abilities to provide responsive early reading programs to both the assessment portfolio product and the action research process.

References

Bear, D., Invernizzi, M., Templeton, S., & Johnston, F. (2000). Words their way: Word study for phonics, vocabulary, and spelling instruction (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River , NJ : Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Beaver, J. (1997). Developmental reading assessment. Parsippany , NJ : Celebration Press.

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 80 (2), 139-144.

Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions . Thousand Oaks , CA : Sage.

Creswell, J. W. (2002). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Upper Saddle River , NJ : Merrill Prentice Hall.

Earl, L. M. (2003). Assessment as learning: Using classroom assessment to maximize student learning. Thousand Oaks , CA : Corwin Press, Inc.

Gentry, J. (1985). You can analyze developmental spelling - and here's how to do it! Early Years K - 8, 15 (9), 44-45.

Hensen, R. K. (2001). The effects of participation in teacher research on teacher efficacy. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17 , 819-836.

Kemmis, S. (1983). Action research. In T. Husen, & T. Postlethwaite (Eds.) International Encyclopedia of Education: Research and Studies. Oxford : Pergammon.

Invernizzi, M., Landrum, T., Howell, J., & Warley, H. (2005). Toward the peaceful coexistence of test developers, policymakers, and teachers in an era of accountability. The Reading Teacher, 58 (7), 610-618.

Johns, J., Lenski, S., & Elish-Piper, L. (1999). Early literacy assessments & teaching strategies . Dubuque , IA : Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company

Loman, K. (2002). Assessment & intervention for struggling readers. Greensboro , NC : Carson-Delosa Publishing Company, Inc.

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Washington , DC : National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and Department of Education.

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2003). Early reading strategy: The report of the expert panel on early reading in Ontario . Toronto , ON : Author.

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2005). Education for all: The report of the expert panel on literacy and numeracy instruction for students with special education needs, kindergarten to grade 6. Toronto , ON : Author.

Paris, S., & Hoffman, J. (2004). Reading assessments in kindergarten through third grade: Findings from the center for the improvement of early reading achievement. The Elementary School Journal, 105 (2), 199-217.

Partridge, H., Invernizzi, M., Meier, J., & Sullivan, A. (2003, November/December). Linking assessment and instruction via web-based technology: A case study of a statewide early literacy initiative. Reading Online , 7 (3). Retrieved August 6, 2004, from http://www.readingonline.org/articles/art_index.asp?HREF=partridge/index.html

Randell, B., Smith, A. & Giles, J. (2001). PM Benchmark Kit: An assessment resource . Toronto , ON : Nelson Thomson Learning.

Robertson, C. & Salter, W. (1997). The phonological awareness test . East Moline , IL : LinguiSystems, Inc.

Rosner, J. (1993). Helping children overcome learning difficulties: A step by step guide for parents and teachers (3 rd ed.). New York : Walker & Co.

Sagor, R. (1992). How to conduct collaborative action research . Alexandria , VA : Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Snow, C. E., Burns, M. S. & Griffin , P. (Eds.). (1998). Preventing reading difficulties in young children . Washington , DC : National Academy Press.

Stringer, E. (2004). Action research in education. Upper Saddle River , NJ : Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Walpole, S., Justice, L., & Invernizzi, M. (2004). Closing the gap between research and practice: Case study of school-wide literacy reform. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 20 , 261-283.

Yopp, H. (1995). A test for assessing phonemic awareness in young children. The Reading Teacher, 49 (1), 20-29.

Table 1

Primary-Grade Literacy Assessment Portfolio Skills and Tools

Skill |

Assessment Tool |

Print concepts |

Print concepts assessment (Loman, 2002) |

Phonemic awareness |

Yopp-Singer test of phoneme segmentation (Yopp, 1995) |

Letter-sound identification |

"In-house" district developed letter-sound identification tool |

Sight-word recognition |

"In-house" district developed program-linked sight word lists |

Reading fluency |

Developmental Reading Assessment (Beaver, 1997) |

Reading comprehension |

Developmental Reading Assessment (Beaver, 1997) |

Encoding-spelling |

Gentry developmental spelling test (Gentry,1985) |

Figure 1. Grade-by-grade, term-by-term assessment schedule

Figure 2. Grades 1-3 portfolio summary tracking sheet.

Figure 3. Senior Kindergarten portfolio summary tracking sheet.

Biographical Note:

Arlene Grierson has over twenty years teaching experience with Ontario school boards. Most recently she was a system resource teacher who spent four years providing literacy related teacher professional development. It was in this capacity that she coordinated and facilitated this action research project. Arlene would like to acknowledge the invaluable contributions of the action research group members, for whom pseudonyms have been used throughout this paper. Their expressed concerns were the catalyst for this project and throughout its duration the action research group members' consistently put forth outstanding efforts and remained committed to enhancing their classroom assessment and instructional practices. Currently, Arlene is a doctoral candidate in the Faculty of Education at Brock University . Additionally, she teaches Pre-Service Language Arts and Additional Qualifications Reading courses at Brock University . Her primary research interests include teacher professional development associated with literacy assessment and instructional practices, and teachers' conceptual change processes. Arlene looks forward to continued action research opportunities with teacher practitioners. She can be reached at the Faculty of Education, Brock University , 500 Glenridge Avenue , St. Catharines , Ontario . L2S 3A1. Email: agrierso@brocku.ca

Vera E. Woloshyn is a Professor in the Faculty of Education and Director of the Brock University Reading Clinic. Dr Woloshyn teaches courses in literacy, reading development, reading assessment, cognition and memory, educational psychology and research methodology. Her primary research interests include teacher professional development associated with the development and implementation of effective literacy/learning strategies and teaching methodologies, especially for individuals with learning disabilities. Currently, she is a Board Member for the Learning Disabilities Association of Ontario and President of her local chapter. Dr. Woloshyn is the recipient of several national grants and has authored and/or edited numerous books and peer-reviewed articles. An educator herself, Dr. Woloshyn is appreciative of the many opportunities she has to work collaboratively with educators in field, and as the mother of two school-aged children, is well versed in school life. She can be reached at the Faculty of Education, Brock University , 500 Glenridge Avenue , St. Catharines , Ontario . L2S 3A1. Email: woloshyn@brocku.ca