THE GENESIS OF A HYBRID WRITING INSTRUCTION APPROACH THROUGH ACTION RESEARCH

Alison J. Engemann and Tiffany L. Gallagher

Brock University

Lucie, a Grade Two classroom teacher, and Kate, a university professor, e ngaged in an action research study that linked a trait-based writing instruction approach with a genre-focused instruction approach. To capture the experience, fieldnote observations, interviews and samples of students' work were collected. Lucie recognized the need to augment her initial trait-based lessons and connect the two instructional approaches. Kate affirmed these decisions and documented the efficacy of her hybrid approach. Lucie engaged in reflective practice that was nurtured through the process of action research. Both researchers continue to refine their hybrid model and record their ongoing experience.

Introduction

A review of the literature that explores writing instruction methods, best practices, and resources reveals an array of viable approaches to teach writing (e.g., Calkins, 1994; Graves , 1994; Tompkins, 2000). Beginning writers are especially amenable to writing approaches that provide them with an appreciation for the interrelations of purpose, audience, and form in writing, as well as the mechanics of written work (Tompkins, 2000). But what is an effective approach to teach these formative writers to communicate through written language? This paper will present the experience of a classroom teacher and a university professor, as together they document how two instructional methods were blended and delivered to Grade 2 writers. The effect of this hybrid approach is substantiated, but equally important is the validation of the action research process as the vehicle for curricular and instructional change.

Trait-based Writing Instruction Approaches

Writing is considered to be one of the most difficult skills students are expected to master in elementary school. Presently, there is interest in models of instruction that clearly define the components of good writing, and provide a structure for assessment that connects with identified traits. A trait-based instruction approach accentuates the characteristics of quality writing (e.g. ideas, organization, voice, sentence fluency, word choice, conventions) and encourages students to include these aspects in their compositions (Spandel & Hicks, 2002). Over the past decade, the popularity of the 6 + 1 TRAIT model (Culham, 2003) and its associated analytical rubric have grown among educators in North America . A similar teaching resource, Write Traits ® (Spandel & Hicks, 2002), also provides classroom teachers with lesson ideas and a scoring rubric to address the traits of exemplary writing.

Spandel and Hicks (2002) stress that a trait-based approach is not intended to replace the process approach to writing instruction, but rather to enhance it. According to Spandel & Hicks, the use of a trait-based approach will provide teachers with a structure that supports students' writing achievement. Interestingly, there is a lack of rigorous experimental research around these trait-based approaches, not to mention the reliability of the rubrics that are used to assess student writing composition.

Genre-focused Writing Instruction Approaches

Research on how to teach the various genres of writing can also provide important information about how young children learn to write in different contexts (Chapman, 2002). A genre-focused approach to writing instruction highlights the purpose for writing, the structure and language features of each form, and the processes involved in writing (Education Department of Western Australia, 1994). Learning to recognize and produce different writing genres is an integral part of a child's literacy development (Chapman, 2002).

Beginning writers require instruction and experience in learning how to write a specific genre in order to communicate an idea or a message to others. A focus on genres in writing instruction can provide these writers with the opportunity to write in different contexts. There is evidence that young children acquire the genres that they are given opportunity to use in their writing (Chapman, 1995; Donovan, 2001; Kamberelis, 1999; Wollman-Bonilla, 2000). Interestingly, despite the critical importance of non-narrative genres, many schools lack experience writing in a variety of genres; thus there is an "expository gap" by the time a child reaches Grade Four (Chapman, 2002). Genre-distinct writing does not develop naturally, but instead needs to be taught systematically and explicitly (Chapman, 2002).

The Genesis

As stand alone approaches of writing instruction, there is some evidence that teaching young students about the characteristics or traits and types or genres of composition is important. However, one instructional approach (i.e., trait-based; genre-focused) taught in isolation may be insufficient to provide students with a clear understanding of the craft of writing. In order to present beginning writers with a comprehensive approach, we engaged in an action research study that linked trait-based writing instruction with genre-focused instruction. This hybrid writing instruction approach is unique in the language arts teaching methods literature.

Methods

For practitioners, one of the purposes of action research is to implement and refine new instructional approaches through direct classroom application (Isaac & Michael, 1997). The process of action research includes a continual disciplined inquiry that is conducted to inform and improve educational practice (Calhoun, 2002). Through action research, teachers and educational researchers study their learning contexts for research ideas, explore professional development alternatives and investigate the effects of instructional change on their practice. This form of professional learning is especially common in Ontario where classroom teachers are increasingly viewed as the primary participant in their own growth (Auger & Wideman, 2000). In this way, teachers are able to employ action research methods to ask questions and investigate solutions that augment their professional knowledge and enhance their teaching practice.

This current action research endeavor began with the introduction of a trait-based writing resource. Over a period of time, the classroom teacher discovered that implementation of the resource demanded problem-solving, experimentation, and adaptations; this was initiated by the classroom teacher and supported by the researcher. Across the course of the action research project, the goal remained to deliver the most effective writing curriculum to beginning writers. Accordingly, our guiding research question was, "How do you facilitate effective writing instruction in a Grade 2 class?"

Participants

This research took place in a large suburban school in a Southern Ontario town. The participants included 26 grade-2 students (12 boys; 14 girls) who were homogeneous in ethnic background and spoke English as a first language. Students' academic achievement levels varied from high to low-achieving.

The classroom teacher, Lucie, has 5 years of experience teaching at the Primary and Junior grade levels, as well as Intermediate level French as a Second Language. She is currently enrolled in a graduate level Masters of Education program specializing in curriculum studies. Lucie is an invited university lecturer on topics related to classroom assessment and reporting.

The role of the researcher, Kate, was one of a participant observer. Previously, she was a private practice educational examiner for over a decade. At the present, she is a Professor at a Southern Ontario University. Kate has taught Educational Psychology, and Assessment and Evaluation courses for 5 years. Lucie and Kate had known each other for only a few months; they met when Lucie acted as a grader for a university research project.

Data

This study took place over the course of an academic school year in which multiple forms of data were collected. Lucie was interviewed by Kate during the second and third terms of the school year. These 90-minute interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed.

The researcher took field notes on 8 different occasions during Lucie's writing lessons throughout the two terms. These handwritten notes were shared with Lucie after each observation session, in order to confirm the accuracy of the researcher's interpretations. Lucie's lesson plans were made available to the researcher before, during, and after the observation periods.

Students' documents were collected across the entire period of research. These documents included their daily seatwork, writing organizers, poster presentations, and rubric evaluations.

Data Analyses

The interviews were transcribed and the data was then coded with coloured highlighters to sort out the general discussion topics. Lucie and Kate independently completed the coding and then collaborated to confirm the categories that emerged from the data. The categorical clusters were collapsed to form general patterns (Bogdan & Biklen, 1998; Creswell, 1998; Miles & Huberman, 1994).

The field notes and documents were used to corroborate the patterns found from the verbal data. The field notes were coded as documentation of Lucie's teaching interactions with her students and were used to confirm her perceptions of instructional effect (Bogdan & Biklen, 1998; Cole & Knowles, 1993; Miles & Huberman, 1994). To lend credibility to the study, Lucie's lesson plans and the students' documents were used to verify the interview and field note data. The themes that emerged from the data, illustrated the genesis of a hybrid writing instruction approach.

Findings

As university faculty, Kate had been actively pursuing a research agenda in her field of interest: writing assessment and instruction. In particular, she was part of a research team that was investigating the efficacy of a trait-based writing resource. Lucie was hired as a grader to assist with evaluating students' writing samples. This opportunity piqued Lucie's interest in the trait-based approach and assessment rubric. She was eager to gather instructional materials as she was assigned to teach Grade Two for the first time, and she perceived that this resource could be used as part of her writing instruction program:

I was really excited about using this approach. I thought to myself that this was something that would actually help the kids, not only with spelling and grammar, but also around how to put a piece of writing together. (Lucie, Interview 1, p. 2 of 47)

Kate also held naïve optimism that the trait-based writing approach would be the panacea to teach beginning writing; the university research team had only started to cull their data on the approach and results were unavailable.

Not long after the school year started, Lucie found that the approach had limitations and she had to provide extensions for her writing lessons:

I began teaching a trait and found that my students need a lot of instructional time to grasp the topic.One forty minute period on writing an introduction is not sufficient for my students to develop an effective introduction to a piece of writing. ..I spent three or four classes on that one lesson. You can see how time consuming it can become as I had to do the same for the middle part of the story, and then for the conclusion of the story. (Lucie, Interview 1, p. 2-4 of 47)

.students were still not eager to actually write. Students often asked, "So, how many lines do I have to write?" That's not what writing is about. You get an idea and you should want to write about that idea. (Lucie, Interview 1, p. 27 of 47)

Kate concurred and noted that, "The students appear to be uninspired by writing prompts. They seem to hold limited expectations for both the quantity and overall quality of composition" (Kate, Fieldnotes, February 5, 2005). This led to the first phase of this classroom action research: the identification of a problem (Auger & Wideman, 2000).

Ironically, the initial trait-based lessons were well received by Lucie's students and this enthusiasm continued across several lessons. However, Lucie was disenchanted as she perceived that not all of her students were making progress. Specifically, Lucie was frustrated by the fact that many of her students struggled with understanding the traits. Lucie consulted Kate and they concurred that something needed to be modified. Lucie and Kate collaborated to develop and implement a plan of action that would assist her students in increasing their knowledge of the traits of writing; the creation of a plan of action is generally the next phase of action research (Auger & Wideman, 2000). Lucie began to search for extensions to her lessons in order to solidify students' understandings.

Kate was aware of the reality that practicing teachers need guidance and recommendations when implementing a new instructional approach. In particular, Lucie was looking for suggestions on how to contextualize lessons and extend activities in meaningful ways. Kate documented Lucie's self-discovery process:

Lucie recognized that she had to search and add connections between her lessons She realized that her students needed to do more than surface-level recall and recognition of the traits. Through independent research, Lucie, found other strategic aids (i.e., organizers) to add to her lessons. (Kate, Fieldnotes, February 5, 2005)

Lucie also described how she provided extensions and ideas to augment the trait-based instruction. For example, when teaching "organization," she brought in children's literature as illustrations that had good introductions and conclusions.

One of the books that I got was The Z was Zapped by Chris Van Allsberg, to demonstrate sequencing in "organization." We talked about the "organization" of the book and how it flowed from the starting point at 'A,' to the concluding point at 'Z.' (Lucie, Interview 1, p. 35 of 47)

Kate attested to Lucie's instructional effect by noting that before she had extended the lessons some students had a minimal understanding of an "introduction" to a story. Yet, after a number of weeks of applying the supplementary lessons to the trait of "organization," students' seatwork reflected a more clear understanding of "introduction," and students attempted to incorporate this understanding into their own writing.

After a few months, Lucie was generally pleased with the progress that her students were making with respect to the traits of writing; yet she sensed that her students lacked a general awareness of the communicative purposes of writing. Now, a new problem had surfaced to be addressed collaboratively by Lucie and Kate. Inspired by a conference session that she attended, Lucie pursued an alternative yet complementary approach to fill in these gaps:

I had this epiphany about how we could apply this approach to our current action research. While I was in the session, I thought to myself, "This is something we hadn't realized, but what is really lacking in our approach is it doesn't look at the many different genres of writing and the specific traits in a given type of writing." A trait-based approach is really general. Right now we're looking at traits in any type or writing. That's when I thought, "Wouldn't it be interesting to be able to teach all of the traits, and then apply them to specific genres of writing, such as non-fiction, fiction, and poetic genres?" So what I would like to do now is look at a specific trait, like "organization," teach the lessons that go along with the trait, and then focus on one genre like report writing for example. (Lucie, Interview 2, p. 1-2 of 7)

This second plan of action was the genesis of the combined instructional approach that Lucie put into effect for the final term of the school year. Lucie realized that her Grade Two students needed to be aware of the distinctions between narrative and expository writing. She perceived that Primary level students have a great deal of exposure to narrative text. In the introductory genre lesson, Kate observed that Lucie was able to encourage her students to draw a parallel between narrative and expository text components. Lucie modeled for her students how to deconstruct the components of a written report with a focus on the trait of "organization":

Using a report that she wrote about "Lions," Lucie made a framework of the components of the report. Students identified the introduction and the other components of the report. One student remarked that the animal in the teacher's sample report was like the main character of the story. (Kate, Fieldnotes, May 13 &16, 2005).

After deconstructing her report, Lucie provided her students with a graphic organizer that she devised for them to use as a framework for their report. This graphic tool was used to guide her students as they researched information. First, students researched information to generate "ideas" for their reports. From text resources, they eagerly gathered data that described their animal and its behaviours. The trait of "voice" was demonstrated in the titles and introductions of the students' reports: creative titles such as, "Ostriches are Far Out," and attention catching introductions such as, "Did you ever wonder how fast a leopard can run?" The trait of "organization" had been covered over the past months, and this was exemplified in her students' understanding of the general structure of text. Across the genre lessons the students also demonstrated their understanding of the other traits of writing in their rough drafts.

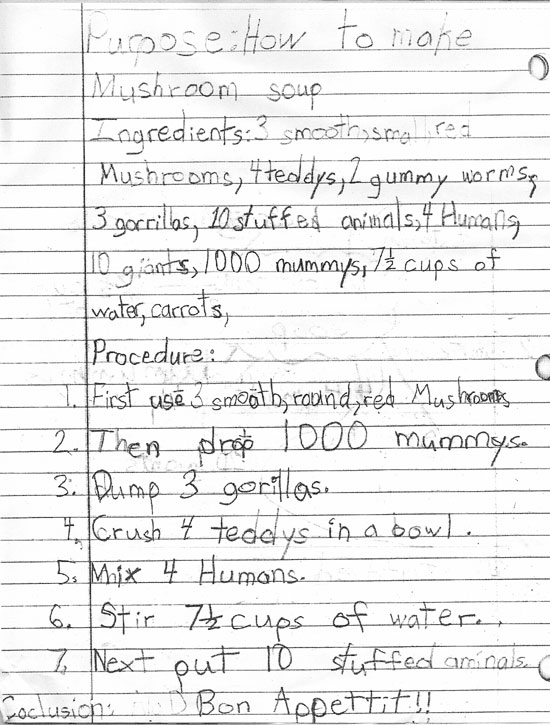

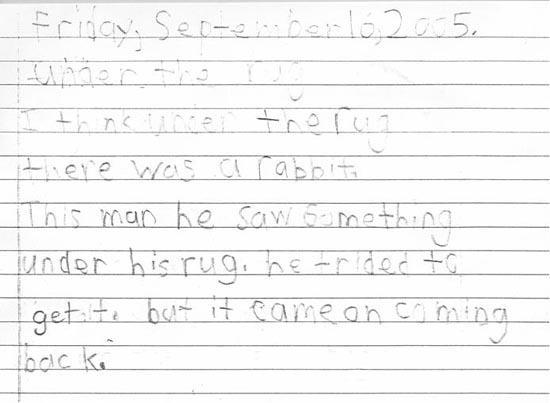

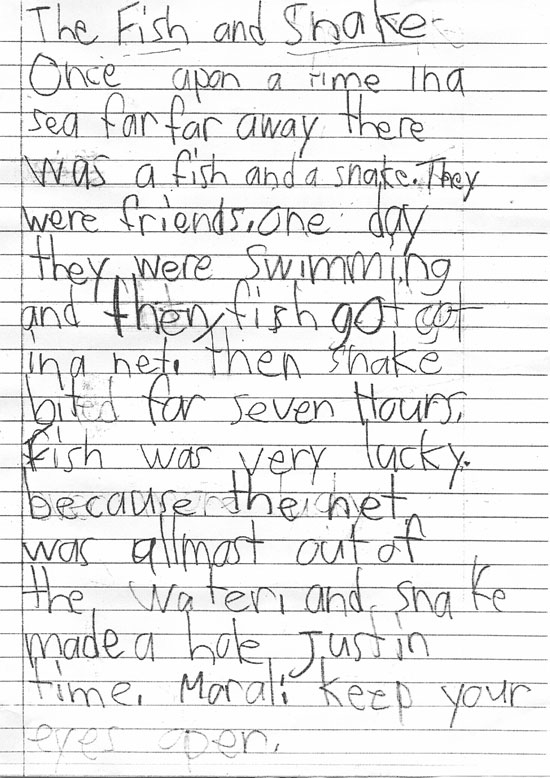

Subsequent analyses (see Engemann & Gallagher, 2006a; Engemann & Gallagher, 2006b) have documented the efficacy of the hybrid approach to writing instruction on the students' writing compositions. The students' writing samples and rubric evaluations have been examined through quantitative analyses (paired samples t-tests, p<.01) and significant growth was evident from pre-test to post-test in both the inclusion of the traits of voice and word choice in their writing (see Figure 1a. Pre-test writing sample with word choice trait and 1b. Post-test writing sample with word choice trait ) and the narrative and expository genres of writing (see Figure 2a. Pre-test narrative writing sample and 2b. Post-test narrative writing sample ). This growth was present when samples were graded on both trait-based rubric and genre-based rubrics.

Figure 1a - Jordan 's pre-test writing sample with word choice trait

Figure 1b - Jordan 's post-test writing sample with word choice trait

Figure 2a - Chris' pre-test narrative writing sample

Figure 2b - Chris' post-test narrative writing sample

To summarize, during the first term of Grade Two, Lucie had provided students with instruction on the traits of writing (Spandel & Hicks, 2002) which were extended and reinforced through the second term. Then Lucie decided to incorporate a framework for report writing (Education Department of Western Australia, 1994) and integrated a discussion of the traits of writing across her report genre lessons. The traits of "ideas," "organization," and "voice" were emphasized in her lessons that addressed "context" (purpose + audience), "structure" (form of text), and "composition" of reports. During the revision process, the traits of "sentence fluency," "word choice," and "conventions" were the focus.

After reflecting on the perceived success of combining two writing instruction approaches, Lucie and Kate devised a year-long plan for writing instruction that Lucie would use for her next year teaching Grade Two writing curriculum:

Each month I will look at one trait and one genre, and then move on to a different trait and a different genre. For example, this time I will focus on the trait of "sentence fluency" along with report writing. I will then focus my assessment on "sentence fluency" within a report. (Lucie, Interview 2, p. 5 of 7)

Conclusion

The process of reflection that Lucie and Kate engaged in is a valid one to advance their respective understandings of effective practice. Reflection is a cognitive process in which individuals are actively involved in addressing practical problems and contemplating possible solutions (Schön, 1987). In this case, the practical problem was that Lucie perceived that the single writing instruction approach that she was using was ineffective. According to John Dewey (1933), the concept of cognitive reflection as a problem-solving strategy is a thought process resulting from a state of doubt and leading to a search for new information. Lucie experienced this doubt in her practice and searched for new resources and instructional approaches to solve her practical problem. Schön (1987) has elaborated on Dewey's concept of cognitive reflection and stated that teachers' beliefs about the outcomes of their practice are "reflective practices." Schön states that teachers need to be reflective during and after teaching as a means of improving their practice. This type of reflective practice is what Lucie engaged in, and what was nurtured through the process of action research.

I think I've grown as a writing teacher because I had to do some of my own research, and come up with some different and interesting ways to involve my students in this process.Now I can actually share some of what I've found with other educators. I feel good that I've been able to expand on my knowledge of writing instruction and prepare these students for their next academic year. I'm really interested in improving upon my instructional approach too. On a larger scale, I would like to provide teachers with this comprehensive writing approach that will cover all facets of writing instruction (Lucie, Interview 1, p. 41-42 of 47).

This action research project began with the simple goal of documenting the implementation of a single writing instructional approach. Even though the classroom teacher, Lucie, was new to teaching at the primary division, she was attuned to the learning needs of beginning writers and the pedagogical limitations of the resource and approach that she was using. First, she augmented the resources and extended the lessons. Then she married the trait-based approach with the complementary genre-focused approach. Throughout this process, the researcher, Kate, acted as a supportive colleague and documented Lucie's professional growth.

Basically, this action research has come full circle as the original question "How do you facilitate effective writing instruction in a Grade Two class?" exists in a more robust form: "Is an integrated instruction approach that links the traits of writing composition (ideas, organization, voice, word choice, sentence fluency, conventions) with the genres of writing (e.g. reports, narratives, recounts, expositions) an effective approach with Grade Two writers?" We pose this question to writing teachers to explore and document in their own classrooms. At present, we are continuing to explore this question in a rigorous manner.

References

Auger, W., & Wideman, R. (2000). Using action research to open the door to life-long professional learning. Education , 121 (1), 120-127.

Bogdan, R. C., & Biklen, S. K. (1998). Qualitative research for education . Needham Heights , MA : Allyn & Bacon.

Calkins, L. (1994). The art of teaching writing . Portsmouth , NH : Heinemann.

Calhoun, E. F. (2002). Action research for school improvement. Educational Leadership , March. 18-24.

Chapman, M. (1995). The sociocognitive construction of written genres in first grade. Research in the Teaching of English, 29 , 164-192.

Chapman, M. (2002). A longitudinal case study of curriculum genres, K-3. Canadian Journal of Education, 27 , 21-44.

Cole, A. L., & Knowles, J. G. (1993). Shattered images: Understanding expectations and realities of field experiences. Teaching and Teacher Education, 9, 457-471.

Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design. Thousand Oaks, CA : Sage.

Culham, R. (2003). 6 + 1 traits of writing. New York : Scholastic.

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think, a restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. New York : Academic Press.

Donovan, C. (2001). Children's development and control of written story and informational genres: Insights from one elementary school. Research in the Teaching of English, 35, 394-447.

Education Department of Western Australia (1994). Writing Resource Book. Portsmouth, NH : Heinemann.

Engemann, A. J. & Gallagher, T. L. (2006a). Genres and Traits: Linking Two Writing Instruction Approaches. Paper Presentation at: 51 st Annual Convention of the International Reading Association (IRA), Chicago, IL .

Engemann, A. J. & Gallagher, T. L. (2006b). Traits and Genres: A Dual-Approach to Writing Instruction . Paper Presentation at: Annual Congress of the Canadian Society for the Study of Education (CSSE), Toronto, ON.

Graves, D. (1994). A fresh look at writing. Toronto : Irwin Publishing.

Isaac, S., & Michael, W. B. (1997). Handbook in research and evaluation. San Diego, CA : Edits.

Kamberelis, G. (1999). Genre development and learning: Children writing stories, science reports and poems. Research in the Teaching of English, 33, 403-460.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: A sourcebook of new methods . Beverly Hill, CA: Sage.

Schön, D. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. San Francisco : Jossey Bass.

Spandel, V. & Hicks, J. (2002). Write traits classroom kits . Wilmington , MA : Houghton- Mifflin Co.

Tompkins, G. (2000). Teaching writing (3 rd Ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ : Merrill.

Wollman-Bonilla, J. (2000). Teaching science writing to first graders: Genre learning and recontextualization. Research in the Teaching of English, 35, 35-65.

Biographical Note:

Alison Engemann is a full-time Classroom Teacher with the Niagara Catholic District School Board. She is presently teaching Grade 2, although she has taught Grades 1-8 FSL and Grades 4 through 6 (regular classroom). She holds a BA Honours in French and her Bed. Alison is a Master of Education Candidate at Brock University with a focus in the area of Curriculum Studies. Her current research interest is in the acquisition of writing skills in primary students, writing instructional within the primary classroom, and writing curriculum and resources.

Tiffany Gallagher teaches Educational Psychology in the Pre-service Department of the Faculty of Education, Brock University . Recently, she completed her doctoral studies on the effects of tutoring students with learning difficulties and the associated experiences of their literacy tutors. Professionally, Tiffany has been an administrator in private practice supplemental education for over a decade. Tiffany's current research interests include literacy assessment, reading and writing strategy instruction, and the role of the in-school resource teacher.

Both can be reached at the Faculty of Education, Brock University , 500 Glenridge Avenue , St. Catharines , Ontario . L2S 3A1.