MOTIVATION AND ENGAGEMENT IN YOUNG LEARNERS: AN ACTION RESEARCH PROJECT

Grace Jones

Chilliwack School District , British Columbia

Abstract

This research study of goal-setting with early intermediate Grade 4 and 5 students was conducted to determine whether teaching goal-setting skills and strategies would enhance student success in specific assignments. An available curriculum, the BC Life Skills program, provided strategies that students used to complete projects in Science and Language Arts. Findings indicate that explicit instruction in vocabulary and process was required before students applied the skills to tasks in writing and organizing, resulting in successful completion of the projects by the majority of students. This research supports the idea that having competency in goal-setting can contribute to quality completion of work in young learners.

Introduction

This action research was undertaken to address low levels of motivation among many young learners, particularly those arriving in my early intermediate classes, grades four and five, already testing well below grade-level expectations in literacy and numeracy. Many of these students were observed to lack engagement and were discouraged by the demands of the curriculum, resulting in low motivation.

One goal of my research was to examine whether providing students with a set of skills and strategies for goal setting would result in higher completion rates of class assignments. I investigated several recommended curriculum resources on goal-setting available in my district and looked at documents from the BC Ministry of Education related to Personal Planning and Special Education to find learning outcomes related to goal-setting. In the course of the project students were taught skills, related to these outcomes, that they could apply to two specific assignments, one in Science and one in Language Arts.

Another goal of the research was to look at how meeting goals for assignments would affect student motivation, or engagement, with their learning. Was there a way to equip these discouraged young learners with tools to help them succeed in daily class work in such a way that they would become excited about learning?

kFinally, an essential part of this action research was to look at my role as the teacher. How much would my practice need to change as I incorporated these lessons into my classroom repertoire?

Review of Literature

In preparation for the research project my review of the literature led down several paths. One was to investigate what had been done in the area of teaching motivation. Another was to look at theories about how children learn and acquire knowledge. Yet another looked at teaching methodologies in the area of literacy, as both curriculum applications would involve reading. I will touch briefly on each of these paths.

Ryan and Deci (2000) developed a theory of self-determination that looks at the difference between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and how personal determination is exhibited through behaviour. Their testing was designed to monitor and code behaviours to see whether extrinsic or intrinsic rewards resulted in better motivation among their students. They concluded that self-determination comes as a result of understanding one's own process of learning. I was interested in knowing if students would become better motivated if they received a reward from me or if doing better as a result of using goal-setting strategies would help them feel more successful and, therefore, more engaged in learning. Ryan and Deci's (2000) work was done with university level students, mostly in the medical field, but I felt that the general principles of their study could be applied to younger learners. Other studies on self-determination by Wehmeyer (1997, 2003), Standage, Duda & Ntoumanis (2005), and Anderson & Midgeley (1998), covered different topic areas; special education, physical education and middle school students, respectively, but the conclusions were the same; that students could and should be taught skills in self-determination. They also concluded that students who had skills in setting goals, and who recognized the need to have a process in place to fulfil those goals, were more successful in school and in making future life decisions.

Vansteenkiste, Simons, Lens, Sheldon & Deci (2004) looked at the teacher's role in promoting motivation, focussing on how the teacher mediates the learning context. They found that teachers play a significant role in motivating students, by guiding them through the learning process. Ryan and Deci (2000) point out the importance of the teacher having a personal connection to students in the learning situation. Other writers who looked at the teacher's role include Arhar and Buck (2000), who state ".teaching is a moral commitment to the democratic relationships between teachers and learners," (p.328), Collins (2004), who says, "We make constant renewal of our professional and moral promise to do our best in regards to children.." (p. 351), and Huitt (2004), who relies heavily on Maslow's work on how teachers can determine student learning needs, which he divides into deficiency needs (bodily comforts, hunger, thirst, safety and security, belonging and acceptance, and esteem) and growth needs (cognitive or the need to know, aesthetics such as symmetry, order and beauty, self-actualization and fulfilment, and self-transcendence, the connection to something beyond oneself). The conclusion was that if the teacher fails to address the deficiency needs of the student first, then it will be difficult to progress to the growth needs.

Based on the work of developmental psychologist John Flavell, Livingston (1997) defines metacognitive theory in a way that it: "involves active control over the cognitive processes engaged in learning. Activities such as: planning, how to approach a given learning task, monitoring comprehension, and evaluating progress toward the completion of a task are metacognitive in nature" (p. 1). When considering metacognitive theory, she claims that teachers need to teach children how to learn before teaching them what to learn. Moore (2004) connects metacognition theory to constructivism and how students' thinking helps them construct knowledge within the context where the learning takes place. Hacker (1998), states, ".the promise of metacognitive theory is that it focuses precisely on those characteristics of thinking that can contribute to students' awareness and understanding of being self-regulatory organisms, that is, of being agents of their own thinking." (p.7). This connects to Ryan and Deci's assertion that students must feel some sense of autonomy in order to be engaged. Several other studies, (See for example, Pierce (2003), Wahl (2004), Wood & Endres (2004), Walsh & Smith (2003) and Schwarm & VanDeGrift (2002)), all conclude that students need to have certain tools to develop metacognition and that thinking about how they learn enhances what they learn.

When I looked at methodologies in reading, there was no shortage of work done in pedagogical approaches to teaching reading, so I concentrated on those studies that also looked at metacognition as part of their approach. Collins (1994) identified how students interpret and understand text by how they interact with it. She emphasizes the active role students must take in reading in order to access the knowledge within it. Chan (1992), in considering metacognitive aspects of reading, focuses on student perceptions about their abilities. She found that how students perceive themselves affects their performance. Wren (2002) refutes many of the standard assumptions about reading instruction that he feels impede student progress and emphasizes the teacher's role in student success. He concludes that the primary impact on student performance is the quality, knowledge and sophistication of the teacher. Wray and Medwell (1999) also concluded that it is teachers who make connections between the goals of literacy and the learning activities which influence student success in reading.

The two points that were most significant for me from this review of the literature were that teachers play a significant role in creating the context for learning and that there are tools that can be taught to help struggling students be successful. As mentioned earlier, most of the studies involved students who were middle school age or older and it was clear that there was little research involving work with students in early grades on engagement and motivation, so I was curious to know if my findings would be similar to studies done with older students. I also felt that this was an area that needed to be investigated because many children are opting out of formal education at a young age. If students are already below grade level expectations at the age of ten, what does that mean for their continued learning success as teenagers or adults? I was also challenged by the role I could play in setting up a learning environment where students would feel they were acquiring skills that would help them complete work and improve their academic standing.

This led to the following research questions.

1. How did my actions, as a teacher, affect the motivation of my students?

2. Could I develop strategies that would encourage my students to be more self-determined and create a context where engagement would happen?

3. How would focussing on goal-setting and student engagement change the behaviours and attitudes of my students so they completed more work and improved their academic standing?

Design and Methodology

With these questions in mind I set out to design my action research project. I first sought lessons on goal-setting. Of the recommended resources available in my district, I chose to use the BC Life Skills program (BC Ministry of Education, n.d.). This is a resource designed to support the Personal Planning curriculum for Grades 1-7 and has modules on personal growth, setting goals, planning and problem-solving. I focussed on the module entitled, Setting Goals, Making and Enacting Plans, designed to support the Personal Planning IRP (Integrated Resource Package - these are the Curriculum guides for British Columbia 1995). It consists of a set of eight core lessons on goal setting with an additional ten lessons to further explore the core concepts. (See Figure 1)

Core Lessons: • What is a goal? • Setting a classroom goal • Working cooperatively to achieve a class goal. • Setting individual goals. • Famous Explorers made plans too. • Reaching your goals • Planning for Success • Making plans to achieve a goal.

|

Figure 1 (selected from BC Life Skills Table of Contents, pp. I-II)

I chose this resource because it presented concepts and skills in a way I felt would be accessible to my students and it came with a variety of activities to develop a better understanding of the processes involved. It allowed for diversity in instruction and in learning styles. It relied on a formative type of assessment which fit well with the methods I wanted to use in collecting my data.

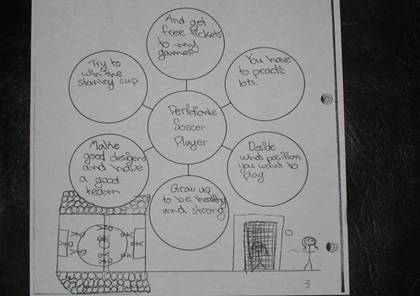

Sample of goal-setting web template from Lesson #1, BC Life Skills

The study was conducted in a Grade 4/5 class from January - March 2006. Data collection was completed to coincide with the end of the second reporting period. Of the twenty-six students in the class, sixteen gave permission to be part of the data collection process. This included seven students in Grade four and eight students in Grade five. There were nine females and six males. The students ranged in academic ability from the lowest to the highest reading levels in the group and included four students on IEPs (Individual Education Plans). IEPs in British Columbia are written for any student who is significantly below grade level expectations in basic skills, usually identified through testing such as the K-TEA and Peabody , or any student who has been identified as gifted. All students in the class received the same instruction whether they agreed to participate in the research or not. All students completed the final survey. Because no names were placed on the survey the results reported include all students who responded.

In structuring my project I created a plan where lessons on goal setting were interspersed with the application of each goal setting concept to an actual learning activity. This plan created a connection between the theory, or concept, presented and the practice, or assigned task. I began with four lessons that identified the key terminology and took students through activity frameworks that introduced them to the goal setting process. I then introduced the two curriculum projects they would be doing. The projects were to complete a Science research project of their choice and present it in a poster or written report format, and a Language Arts project, to write and illustrate a children's book suitable for a child in Grade One or Two.

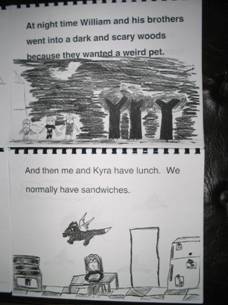

Two excerpts from student story books showing text and illustrations.

The goal setting framework was used to plan their progress as they completed these two projects. Students participated in setting the criteria for their projects and they monitored their own progress from start to finish, by doing weekly progress checklists and writing about their work in their journals. The frameworks increased in complexity as they moved through the lessons. (See Figure 2)

Goal Setting Chart A - First Lesson • My goal is. • I'm going to start by. • I'll know when I've met my goal when. • Date set / Date completed

Goal Setting Chart B - Fourth Lesson • My goal is. • I'm going to start by. • I can get help by. • I'll know I've met my goal when. • Date set / Date met • My (_________) helped me reach my goal by.

Goal Setting Chart C - Eighth Lesson • I am interested in achieving the following short-term goals: a) b) c) 2. I will focus on the following goal first. 3. These are the difficulties or challenges I may face in achieving this goal. • This is what it would be like if I achieved this goal. • I need to take the following steps to reach this short-term goal. • What I need to do -----Who/What can help me |

Figure 2 (BC Life Skills, pp. 7, 14, and 44)

Throughout the time period used to complete these projects they were frequently asked, by the teacher, to reflect on the work they were doing and to recall vocabulary and processes used in their work. This was done through journal writing and class discussion, as well as the completion of a mid-assignment progress assessment, conducted by the teacher as an interview with each student. (See Figure 3)

Making and Implementing a Plan: Assessment To What Degree. Comment /Evidence |

• was there evidence of a plan? • was the plan realistic - timeline, materials? • did you stick to your plan and project? • any new ideas or changes needed? • did you keep to the timeline? • will you meet the deadline date? |

Figure 3 (BC Life Skill, p.21)

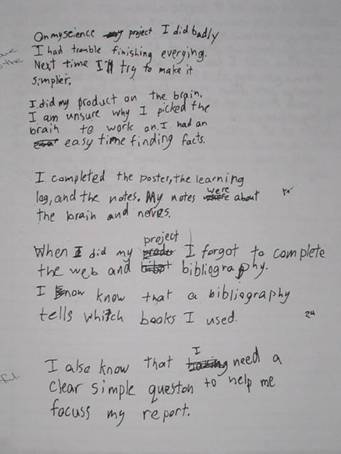

Excerpt from student journal describing their progress

The data collected included all their assignments from the goal-setting lessons, student journal entries and the completed curriculum projects in Science and in Writing, as well as my own journal and field notes. At the conclusion of the data collection process students were asked to complete a survey that assessed their understanding of goal setting and how it could be used to plan and organize their work so each project was completed. (See Appendix 1)

Results

I chose to use qualitative data, such as student journal writing and interview notes, to assess student learning and as evidence of students' understanding of the concepts and processes for goal-setting. I tracked the transfer of knowledge from the goal-setting exercises to actual curricular assignments through observation during class and student journal entries. I coded each student entry that mentioned the vocabulary used to describe a specific skill they had learned and the application of each process to their work. I looked for student references related to their feelings about the work they were accomplishing and any comparisons they made to how using the planning strategies they had been taught was different than methods they had used before. I also noted any references to how they expected to use these strategies in their future work.

I found that there was an initial hurdle in student understanding of the vocabulary used in the lessons and I had to teach each new concept. Each step in the planning process had to be explained carefully so students could move comfortably from one to the next. The templates that came with the lessons assumed that students would be familiar with things like webs, VENN diagrams, and Cornell note-taking and would be able to complete them independently, but I found I had to teach each of these processes and model how they should be done. In my journal from February 13/06 I wrote,

I am frustrated by the materials I have chosen to use. There is an assumption that students know the terms, have experience doing the activities, and are able to work independently on the reading and writing tasks. I have had to adapt every lesson to make sure vocabulary is understood. I am spending time teaching how to do the activities. I am having to help many students read the material.

As the students began to apply the frameworks to actual class work there was a division between those who used them independently and those who did not. About half the class made journal entries that indicated they were comfortable using the forms I provided, and half who were still confused by them. In some cases a student would be absent and miss a step in the process which showed up in their planning sheets. Some students chose not to use the frameworks unless I helped them complete them.

Although every student completed both projects and all of them were completed by the due date I had set, which was a new phenomenon for me, it was clear that only a portion of the class had internalized the knowledge and was comfortable using the planning process independently. As a class, we had written criteria for the writing, based on the Performance Standards for Writing from the BC Ministry of Education (2000), and the finished books were marked on a four point scale. A brief example of how these were rewritten is shown in Figure 4.

From Quick Scale: Grade 4 Writing Stories (BC Performance Standards: Writing (2000) Fully Meets Expectations: The story is complete and easy to follow, with some interesting detail. Shows growing control of written language, few errors.

|

From Classroom Criteria: Story Book project Fully Meets Expectations: • story is complete and makes logical sense • setting and characters are described in detail • spelling and punctuation are correct |

Figure 4

Thirty percent of students received a two, indicating they were only partially meeting the expectations; forty-eight percent received a three, indicating they were fully meeting the expectations, and the remaining twenty-two percent received a four, indicating they exceeded the expectations.

On the final survey 70% of the students indicated that they felt goal-setting helped them in school, which correlates to the 70% who met, or exceeded, the expectations. Another 20% felt that setting goals helped them to remember things they had to do. Students were able to articulate which parts of the process had been helpful and how the skills affected them personally.

Excerpt from student journal which shows the use of new vocabulary to describe progress

In analyzing the student responses on the survey and looking at their completed work, I could also examine my own role in the process. I questioned whether the increase in completed work was due to student knowledge of the goal setting process or because I was consistently reminding them about timelines and deadlines. I realized that I was structuring my days to include adequate time for the students to work on their projects and I was spending more time having individual conversations and tutorials with students.

In hindsight I can see that teaching goal setting skills to young students is important and valuable as it increases their repertoire for learning, but it is crucial that the teacher be involved, on a day-to-day basis, in conversations with students about their work. This is especially important with young learners who often lack the vocabulary to express their difficulties in learning and who will often not discuss learning with their peers, unless prompted to do so.

To illustrate this I will summarize a conversation I had with three boys who were having some difficulty breaking their research project into steps. I knew that all three of these boys were expert video game players and I asked them to imagine the project as if it was a game and each step in the process was a new level of the game. A few days later I wrote in my journal the plan they had submitted and my comments,

Their plan:

Choose the topic |

10 points |

Intro level |

Write your question |

10 points |

Level I |

Design an outline of project |

20 points |

Level II |

Research - collect information |

20 points |

Level III |

Sort info - choose what to use |

20 points |

Level IV |

Complete poster or paper |

20 points |

Mastery Level |

Bibliography and notes submitted |

10 points |

Bonus Round |

The game analogy seems to work for most of the boys in my class. They seemed to see that each level required an increased amount of effort. Some did not complete the bonus round and submit a proper bibliography, but they grasped that it was important. Each level had a maximum number of points so that the total was 100, with a bonus of 10 extra. |

||

What I found interesting was that they had shared this plan with their friends in the class and several of the other boys adopted the same format. This was, I felt, a transfer of their understanding of the planning process, to be able to explain and teach it to someone else.

At the conclusion of the study I felt that my research questions had been answered. I was aware that my actions affected how students approached their work - spending more time in individual conversations built closer relationships to students. Making personal connections to students and discussing their progress with them regularly helped them keep focussed and on track with their assignments.

Providing students with instruction about goal-setting did result in more consistent work completion. Students did become more self-determined after being taught these strategies - there was a transfer of knowledge and evidence of an internalization of skills in the increased use of the planning process, not just for the two assigned projects in the study, but in other work as well. In their journals, many students made goal statements about math or reading, as well as non-academic goals, like learning to swim. Student behaviours changed as they met goals and realized they could complete a complex assignment successfully. Journal entries indicated that many students felt they had done better work than they were capable of before. Students expressed pride in their work and commented on enjoying doing the projects.

My conclusion is that specific skill instruction in goal-setting is beneficial in helping students plan and organize their work in a way that allows them to complete assignments. I found from my observations of student interactions that they were highly engaged in the work they were doing and proud of their accomplishments. When I informed the class that everyone had completed their book on time, there was a loud cheer and lots of back-slapping and congratulations being passed around. Copies of their children's books were kept in the class and were a popular reading item for the rest of the year. They also enjoyed sharing their story books with students in the primary grades.

Reflection

Throughout the project I had to adjust my expectations and re-evaluate the data I was collecting to make sure I was addressing my original questions. I realized early on that I would have to look at my own role in the entire process and by the end my focus had become largely a self-study. I learned a great deal about my own habits as a teacher, and I had to change many of the ways I did things to accommodate the changing dynamic in my classroom.

As a result of this experience I have come to value interactive time in the classroom. I find myself engaging in individual conversations throughout the day. I believe this personal connection to my students is the most valuable result of my research. This has changed how I deliver curriculum, evaluate student work, schedule my day, and arrange the physical space in my classroom.

I believe that student engagement in learning is connected to having strong relationships between the teacher and the students, as well as between student peers. For students to have successful experiences at school they need a set of strategies to allow them to work with the curriculum, break down tasks and complete their work. The teacher plays a very important role in establishing the context where this can happen.

There is a need for further study into the role of the teacher in motivation, particularly with young learners. As stated previously, ".teaching is a moral commitment to the democratic relationships between teachers and learners." (Arhar & Buck 2000 p.328). Part of that moral commitment is to make sure those relationships lead to success for students. Programs and curriculum resources are only useful as methods of presenting knowledge or skills. They are not enough without the active mediation of the teacher, who creates the environment for learning, and who guides the student to further understanding about the work and the processes needed to accomplish that work.

I have found the action research process to be a valuable personal growth experience. After sixteen years in practice, I find that I am more excited about teaching than ever. I have a renewed sense of purpose. I will continue to explore the possibilities for learning that my research has introduced me to and I will continue to look for ways to engage my students in their own learning.

References

Anderman, L.H. & Midgley, C. (1998). Motivation and Middle School Students. In Eric Digest, June 1998, EDO-PS-98-5. Retrieved 23/12/05 from http://ceep.crc.uiuc.edu/eecearchive/digests/1998/anderm98.pdf

Arhar, J. & Buck, G. (2000). Learning to look through the eyes of our students: Action research as a tool of inquiry. Educational Action Research, 8(2), 327-339.

BC Life Skills Program Organizer: Understanding Oneself, Setting Goals Making and Enacting Plans, and Solving Problems and Making Decisions. BC Ministry of Education Curriculum Branch, Victoria , BC and Rick Hansen Institute, Vancouver , BC .

BC Performance Standards: Writing. (Feb. 2000). BC Ministry of Education, Student Assessment Evaluation Branch, Province of British Columbia .

Chan, L.K.S. (1992). Causal Attributes, Strategy Usage and Reading Competence. Paper presented at the AARE/NZARE Joint Conference, Geelong , Victoria , November 22-26, 1992. Retrieved 12/23/05 from www.aare.edu.au/92pap/chan/92255.txt

Collins, N.D. (1994). Metacognition and Reading To Learn. In ERIC Digest, ED376427. Retrieved 12/23/05 from www.ericdigests.org/1995-2/reading.htm

Collins, S. (2004). Ecology and ethics in participatory collaborative research: an argument for the authentic participation of students in educational research. Educational Action Research, 12(3), 347-362.

Hacker, D. J. (1998). Metacognition: Definitions and Empirical Foundations. University of Memphis website. Retrieved 12/23/05 from www.psyc.memphis.edu/trg/meta.htm

Huitt, W. (2004). Maslow's hierarchy of needs. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta , GA : Valdosta State University . Retrieved 12/23/05 from http://chiron.valdosta.edu/whuitt/col/regsys/maslow.html

Livingston, J.A. (1997). Metacognition: An Overview. Retrieved 12/23/05 from www.gse.buffalo.edu/fas/shell/cep564/Metacog.htm

Moore, K. C. (2004). Constructivism & Metacognition. Tier1 Performance Solutions , Retrieved 12/23/05 from www.tier1performance.com/Articles/Contructivism.pdf

Peirce, W. (2003). Metacognition: Study Strategies, Monitoring, and Motivation. Text version of workshop presented Nov. 17, 2004 at Prince George Community College . Retrieved 12/23/05 from http://academic.pg.cc.md.us/~wpeirce/MCCCTR/metacognition.htm

Personal Planning K-7 Integrated Resource Package . 1995. Province of British Columbia , Ministry of Education, Curriculum Branch.

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, pp. 54-67. Retrieved 12/21/05 from http://www.idealibrary.com

Schwarm, S. & VanDeGrift, T. (2002). Using classroom assessment to detect students' misunderstanding and promote metacognitive thinking. Retrieved 12/23/05 from www.cs.washington.edu/research/edtech/publications/sv02-icls.pdf

Standage, M., Duda, J.L., & Ntoumanis, N. (2005). A test of self-determination theory in school physical education. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 75(3), September 2005, pp. 411-433. Retrieved 12/23/05 from www.ingentsconnect.com/context/bpsoc/bjep/2005/00000075/00000003/art0005

Vansteenkiste, M, Simons, J., Lens, W., Sheldon, K.M., & Deci, E.L. (2004). Motivating Learning, Performance, and Persistence: The Synergistic Effects of Intrinsic Goal Contents and Autonomy-Supportive Contexts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(2), 346-360. Retrieved 12/21/05 from www.psych.rochester.edu/SDT/documents/2004VansteenSimLensSheldonDeci.pdf

Wahl, J. (2004). Metacognition. San Diego State University . Retrieved 12/23/05 from http://coe.sdsu.edu/eet/Articles/metacognition2/index.htm

Walsh, M., & Smith, M. (2002) 'I don't want to be here': Engaging reluctant students in Learning in Loughran, J, Mitchell, I. , & Mitchell, J. Learning from teacher Research. New York : Teacher College Press, pp. 57-74.

Wehmeyer, M.L., Agran, M. & Hughes, C. (2000) A National survey of teachers' promotion of self-determination and student-directed learning. Journal of Special Education, Vol. 34, No. 2 , pp. 58-68. Retrieved 8/15.2005 from www.beachcentre.org

Wood, K.D. & Endres, C. (2004). Motivating student interest with the Imagine, Elaborate, Predict, and Confirm (IEPC) strategy. International Reading Association, doi:10.1598/RT.58.4.4, pp. 346-357.

Wray, D. & Medwell, J. (1999). Effective Teachers of Literacy: Knowledge, Beliefs and Practices. International Electronic Journal For Leadership in Learning. Volume 3, Number 9. Retrieved 2/6/06 from http://www.ucalgary.ca/~iejll/volume3/wray.html

Wren, S. (2002). Ten Myths of Reading Instruction. SEDL Letter, Volume XIV, Number 3.

Appendix 1

Survey questionnaire About Goal-Setting - Template

Over the past few months you have been taught about goal-setting and have been introduced to some strategies for setting and meeting goals. Please answer the following questions. Your answers will help your teacher plan for future lessons.

Circle the best response.

• I remember the following lessons about goal-setting:

a) Identifying individual abilities and skills yes no

b) Role models yes no

c) Managing anger/frustration yes no

d) Identifying feelings that help learning yes no

e) What are goals? yes no

f) Making plans to achieve goals yes no

g) Group goals and individual goals yes no

h) Reflecting on a goal that is achieved yes no

2. I use these strategies to plan and keep track of progress on goals I have set:

a) lists yes no

b) Planner yes no

c) calendar yes no

d) friend (study buddy) yes no

e) webs yes no

f) Journal/dairy yes no

g) teacher notes yes no

h) Other __________ yes no

3. These lessons helped me plan to learn. yes no

4. These lessons taught me new things. yes no

5. Being aware of goals helps me in school. yes no

6. Making a plan to learn makes school more interesting. yes no

7. Making a plan to learn is hard to do. yes no

8. I am more aware of making goals now. yes no

9. My teacher helps me think about goal setting. yes no

10. My teacher helps me think about planning. yes no

Please write about what you think about goal setting and whether or not it helps you in school.

Biographical Note:

Grace Jones is a practicing teacher in the Chilliwack School District , a small community about 100 km east of Vancouver , BC . She is a member of the Chilliwack Teachers Association, a member group of the BCTF. She has taught from K-12 and has been a Fine Arts specialist as well as a classroom generalist. She completed undergraduate degrees in Music and Theatre and in Education at UBC and received her teaching certification there as well. She has recently completed her Masters degree in Education, Curriculum and Instruction. Grace is currently involved in a five year research project conducted by Simon Fraser University on Imaginative Education, called LUCID, based on the work of Lev Vygotsky and Kieran Egan. She can be reached at the Chilliwack School District Office at 8430 Cessna Drive, Chilliwack , BC , V2P 7K4 or by e-mail at graciousdecor@msn.com

Grace Jones is a practicing teacher in the Chilliwack School District , a small community about 100 km east of Vancouver , BC . She is a member of the Chilliwack Teachers Association, a member group of the BCTF. She has taught from K-12 and has been a Fine Arts specialist as well as a classroom generalist. She completed undergraduate degrees in Music and Theatre and in Education at UBC and received her teaching certification there as well. She has recently completed her Masters degree in Education, Curriculum and Instruction. Grace is currently involved in a five year research project conducted by Simon Fraser University on Imaginative Education, called LUCID, based on the work of Lev Vygotsky and Kieran Egan. She can be reached at the Chilliwack School District Office at 8430 Cessna Drive, Chilliwack , BC , V2P 7K4 or by e-mail at graciousdecor@msn.com