“HOW I IMPROVED MY TEACHING PRACTIVE IN GRADE 9 BOYS' PHYSICAL EDUCATION TO INCREASE STUDENTS' PARTICIPATION AND ENJOYMENT”

By Tony D’Oria

A research paper submitted in conformity with the requirements

for the Degree of Master of Education

Nipissing University

March 26, 2004

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank a number of individuals for their contributions to this research paper.

Firstly, to Dr. Ron Wideman for his guidance, patience, advice and encouragement over the last two years as this paper was being made. Secondly, to Dr. Tom Ryan, the second reader, for his help and suggestions. Thirdly, to Laura Price at the Nipissing Library for always being kind, prompt, and thorough with my requests for research literature.

My sincere appreciation also goes to my school colleagues who have helped with proof reading, and graphical design. My thanks also go to my critical friend. Your efforts and insights have made me a better teacher.

I would also like to acknowledge my wife, Anna, who always has and continues to support all of my personal and professional endeavors.

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this action research study was to investigate how I can improve my teaching practice in Grade 9 boys’ physical education to increase students’ participation and enjoyment. By investigating my own practice, my hope was to improve the quality of my instruction and the physical education program. The rising number of health problems in today’s youth related to a sedentary lifestyle, makes it critical that they develop an appreciation for physical activity.

This action research included strategic planning, acting, observing, reflecting, and re-planning. Journal entries, audio recordings and student questionnaires that investigated their level of enjoyment and participation were analyzed . Participants included myself, a fellow teacher, and a physical education class of thirty-three Grade 9 boys. I taught this particular class for 5 weeks in order to perform the proposed research. Data were analyzed using the following methods; coding, memos, and summarizing the data. “Triangulation” of multiple sources of data was used to confirm the findings.

The findings revealed both strengths and areas for growth in my teaching practice. The action research process improved my teaching, especially in the areas of planning, acting, and reflection. The results suggested that this group’s level of enjoyment increased when students were given freedom to choose activities, when they were adequately challenged by someone of similar ability, when they received encouragement, and when they did not misbehave. The findings revealed that free play and game situations, novelty, fast-paced lessons, equal play time, skill evaluation, orderly use of equipment, and plenty of gymnasium space improved students’ enjoyment and participation. The implications of this study support a need for the ongoing practice of action research among teachers and a need for further investigations to identify how educators can increase student enjoyment and participation.

APPENDICES

Note All of the researcher’s personal information such as telephone number and email address has been removed from all documents to protect the researcher’s right to privacy. Also removed was any information that would compromise the confidentiality of others.

INTRODUCTION

Background and Significance of the Research Problem

Sometimes during one of my physical education classes, I will look over to the side of the gym wall where a row of students in street clothes are sitting on a long bench, watching as their classmates enjoy an organized game or sport. It saddens me to see part of the class having so much fun, while others sit off to the side as spectators, not participating in that day’s physical activity. As a teacher, I wish I could motivate all my students to participate fully every day, so that they could get the most out of the program. When I look over at that bench, I begin to wonder if my level of instruction is strong enough to reach these students and to instill an appreciation for physical activities and fitness.

For some of these pupils, physical education class may be the only source of physical activity in their lives. This makes my job as a physical educator extremely important. With the increase in time young people spend watching television, playing computer games, and surfing the Internet, there is very little time left to engage in productive physical exercise. It appears our present society is creating a lifestyle that encourages obesity in young people. For example, Amos (2001) explains that research reported through the media by both national and provincial health promotion agencies continually describes youth as being more obese and less physically active than children 20 to 40 years ago. As a result, kids may be on their way to heart disease, osteoporosis and diabetes if the trend continues. It is critical therefore, that different levels of government, including health and education ministers, work together to increase the amount and quality of physical education in schools.

In reality, this is not happening. A recent article in the Toronto Star reveals that many parents rely on schools to provide their children with the required amount of daily physical activity, but cuts to education have forced several schools to actually reduce the amount of physical education taught in class (Grewal, April 6, 2002 , p. A27). It is also common knowledge among physical education teachers in my school board that a number of schools across Canada have either stopped offering or decreased the number of extra-curricular activities. This presents a significant problem to both teachers and students of physical education classes. From a teacher's perspective, there is continuous pressure to whip the youngsters of today into adequate physical shape, but fewer opportunities to do so. From a student's perspective, there is continuous pressure to become physically fit, but fewer opportunities to do so at school. Thus, what I do during the time of my physical education classes has a huge impact on the well-being of my students. I can motivate unmotivated students to become interested so they may change their attitude toward physical fitness and carry a positive approach into adulthood. I can reinforce and encourage already-motivated students to continue to excel in an active and healthy lifestyle. “In a society where technology is ever present and healthy living habits are more and more a matter of individual choice, quality health and physical education is not a luxury, but an absolute necessity” (Deshaises, 2000, p. 10).

Again, if I could get more students off the bench and onto the gym floor, they may experience greater pleasure and satisfaction in the class. I would also believe I was making a contribution to the students’ well being. As Cai (1998) states, “Enjoyment of class is the positive attribute of student emotion as well as the key factor that relates to teaching effectiveness” (p.412). Simply put, what I do in the physical education class should promote maximum participation and enjoyment.

The purpose of this action research study was to investigate the question, “How can I improve my teaching practice in Grade 9 boys’ physical education to increase students’ participation and enjoyment.” Teaching practice includes the planning and implementation of instruction and activities. By researching this question, my objective was to shape my instruction and the physical education program so that my students will enjoy and participate in physical activity.

I considered the literature on physical education and applied various teaching techniques to examine and improve my praxis. Praxis refers to the “inseparability of theory and practice”, which contrasts the objectives approach, and “encourages teachers to be inventive and reflective”(Kirk and Tinning, 1992, p.1). Hopper (1996) provides an even more powerful definition as he states that praxis occurs when “…an individual construes a more enabling sense of the reality of his or her own existence and the existence of others” and that praxis serves “to liberate practitioners from the constraints that limit their practice” (p. 5).

It was also my intent to examine my practice using action research as the basis of my investigation. In essence, action research is something many teachers employ as a tool to improve practice. Hopper (1996) described action research “as an ongoing process in which practitioners develop their practice collaboratively with other practitioners” (p. 4). Hopper identified different phases to action research that progress and continue in a cyclical pattern (see Figure 1). The first phase involves planning, which is designed to implement teacher intents and address concerns from past lessons. The second phase requires acting on the plan. The third phase deals with observing while the plan is being acted upon. It entails self-observation as well as the presence of a colleague who watches as the lesson is being taught. The fourth phase includes the teacher and observer in a reflecting session based on the experiences of the lesson. The fifth phase, re-planning, completes the cycle and is a result of the work that has transpired over the first four phases. In most cases, this re-planning phase will create a revised or new plan based on new concerns.

Figure 1

Hopper’s Phases of Action Research

Tinning (1992) reported that there are very few action research studies within physical education. This may be the case because physical education has tended to rely on a positivistic approach to validate and give credibility to research findings (Hopper, 1996). These approaches typically involve a theoretical construct or hypothesis that can be examined through the collection of quantitative data. This research involved a mixed approach using both quantitative data regarding students’ participation and enjoyment and qualitative data regarding my own observations and reflections and those of my critical friend. My attraction to action research is that it focuses on naturally-occurring, ordinary events in natural settings, and enables the teacher to gain a better understanding of what ”real life” is like (Miles & Huberman, 1994).

From a more individual perspective, McNiff, Lomax and Whitehead (1996) contended that well-conducted action-research can lead to personal development, better professional practice, improvements in school, and making a contribution to the good of society (p.8). They described what I as an educator strive to do each day .

This study was related to the research conducted by Aicinena (1991) who examined several factors that contribute to students’ enjoyment of physical education and the effect the teacher has on their attitudes. The results of his research were informed by questionnaires, critical incident reports, and personal interviews. Similar to his work, this research study investigated several factors related to student enjoyment and participation. Whereas Aicinena studied a wide variety of subjects, this study was limited to boys in Grade 9 with a wide range of physical and cognitive abilities. Data for this research paper was collected quantitatively and qualitatively through attendance and participation records as well as questionnaires and journal entries. Also, the focus of the study was on myself, not the students. Data was collected related to some of Aicinena’s factors (such as teacher behavior and attitude) for the purpose of seeing the impact of the changes I made in my practice.

The elements of students’ participation and enjoyment were vital parts of this research. In fact, one of the assumptions of this study was that enjoyment and participation are inter-related. Current theories support this assumption. As one journal article (George P. Vanier School, 1999) indicates:

When students are encouraged to participate in an activity and gain appropriate skills through experience, it is more likely that they will learn to enjoy the activity as well. And this increases the probability that they will continue to participate in similar activities in the future (p.29).

It is safe to assume, therefore, that participation and enjoyment do go hand in hand. Students cannot enjoy physical activity if they are not willing to participate. Conversely, if a pupil chooses not to participate, the level of enjoyment cannot be measured.

REVIEW OF THE RELATED LITERATURE

This chapter presents information from current literature that relates to physical education practice. It begins with a look into the present day health concerns of children and supplies data that shows an alarming increase in childhood obesity and the related health risks that result from physical inactivity. This leads to discussion of the value of physical education in combating childhood obesity and promoting a healthy, active lifestyle. Next is a focus on the specific role of the physical education teacher and teaching strategies that instill in students an appreciation of physical activities. The chapter concludes with a review of the literature surrounding physical education programming specifically at the secondary school level.

Health Issues Related to Children

More children are obese or overweight than ever before. In fact, the prevalence of obesity in 12 to 17 year olds has doubled over the last 30 years (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1996). This is of great concern because obesity in children is a significant cardiovascular disease risk factor, and the risk continues into adolescence and adulthood if it is not checked during these phases of life. A recent article in the National Post stated that “today’s children could be grappling with heart disease before their teenage years are even finished” (Friscolanti, October 27, 2003 , p. AL1). Similarly, during the last decade, there has been a great deal of concern over the inactivity of today’s youth and the potential health risks of this type of lifestyle (Pangrazi, Corbin, & Dale, 1999, and Baranowski, Thompson, Durant, Baranowski, & Puhl, 1993). Those who are inactive in their teenage years especially, compromise optimal bone formation increasing both the risk and severity of osteoporosis in later life (Pangrazi et al., 1999).

Conversely, regular physical activity has significant health benefits. Even a moderate increase in physical activity has been shown to reduce chronic disease risks including hypertension, type 2 diabetes, high blood lipids, and cardiovascular disease (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1996).

The Value of Physical Education

Research has also shown that physical activity habits learned as a child are predictors of whether or not a particular individual will lead a healthy active life as an adult (Summerfield, 2000; Raitakari et al., 1994). Such findings make the promotion of physical activity among children imperative. Physical education in schools is an ideal avenue to encourage physical activity and develop fitness among youth because, for many children, school will be their only preparation for an active, healthy lifestyle (Summerfield, 2000). The value of quality physical education in school cannot be emphasized too strongly:

Physical education offers many benefits: development of motor skills needed for enjoyable participation in physical activities; promotion of physical fitness; increased energy expenditure; and promotion of positive attitudes toward an active lifestyle. Evidence also exists that physical education may enhance academic performance, self-concept, and mental health (Allensworth, Lawson, Nicholson, & Wyche, 1997).

It is clear that promoting physical activity may have a significant impact on decreasing obesity, chronic disease, and untimely adult mortality.

Teaching Physical Education that Promotes a Physically Active Lifestyle

As a teacher, working with students in a physical education class can be much different from working with them in extra-curricular activities or recreation leagues. Mitchell and Chandler (1993) wrote, “While participation in youth sports is usually a matter of free choice, this is not always the case for students in physical education” (p.120). In Ontario ’s secondary schools, for example, it is mandatory for students to complete a physical education course irrespective of whether or not they wish to participate. The majority of pupils choose to earn this credit in Grade 9. As a teacher, this may be the final opportunity to spark a child’s interest in living a physically active lifestyle. Thus, the variables that drive a person’s motivation to participate must be considered.

One of the greatest challenges for a physical education teacher is to create and foster a positive attitude toward physical activity among students. As Wade (2000) explained:

A child’s attitude towards activity is one that cannot be taken lightly. It is so important that children understand that the choices they make and attitudes they develop now relating to physical activity will affect those that they make as adults. Giving children the opportunity to be active is a start, but by assisting in the motivational process and ensuring that they have positive experiences so that they will want to continue to be active is even more paramount (p.38).

The goal of creating positive student attitudes toward physical activity should take precedence over other goals in developing and implementing physical education programs. In the same article, Wade (2000) revealed some of these goals:

We must ensure that the opportunities that we provide our students with will result in the ability to participate, learn skills, play fair and promote fitness. But most of all, we must ensure students develop a motivation to become active on a daily basis that results in such enjoyment and satisfaction that they will naturally carry on with these positive habits throughout childhood, adolescence and into adulthood (p. 38).

While student participation and enjoyment are paramount, other goals identified by Wade - learning skills, playing fair, and promoting fitness - are important, not only in their own right but also as contributors to improving participation and enjoyment.

Mandigo and Thompson (1998) introduced the concept of a “flow state” (defined as a person’s motivation to do something) and how it intrinsically motivates young people to be physically active. Their study explained that fun (a flow state) is one of the most common motives cited by adolescents for partaking in sports (p.154). It is crucial that physical education students perceive their experiences in physical education classes as enjoyable. Enjoyment of physical education by students is a direct result of the environment created by the teacher. Mandigo and Thompson found that:

Physical activity environments which provide children with a sense of perceived freedom or choice to modify their environment so that the challenges match their individual skill level are more likely to produce flow experiences than environments which are very structured or controlled by others and cause a low perception of control (p.154).

It would appear then, that a student’s perception of his/her skill level is a strong motivator for enjoyment and participation.

Deshaises (2000) identified 3 factors that lead to a physically active lifestyle. Firstly, enjoyment plays a key role in instilling a lifelong appreciation for leading a physically active lifestyle. Secondly, knowledge and values must be acquired throughout students’ school experience to help them develop positive attitudes and habits. Lastly, confidence and competence in physical activity should be established so that health habits can be developed and maintained.

There is no doubt that the type and quality of instruction provided by the teacher has a direct effect on students’ learning. The meta-analysis of sixteen individual research studies that was conducted by Goldring and Tenenbaum (1989) supported this concept. They specifically looked at instruction based on the instructional cues provided to the student, the student’s participation and involvement in the learning activity, the reinforcement the student received from the teacher, and the feedback supplied by instructors for error correction.

In a later analysis, Behets (1997) broke down the role of teaching a physical education class into two parts: active learning time and instruction time. He concluded that “effective teaching is characterized by a lot of practice time and limited instruction and management… physical education is ‘learning by doing’” (p.215). While this can be helpful information to physical educators, it does not offer strategies for improving student participation. Also, the preceding studies did not take into account the physical ability or skill level of a student. It is essential to note that because “some students lack confidence in their ability to perform motor skills, physical educators must become proficient at encouraging and reinforcing student involvement in activities that lead to competent performance” (Misner and Arbogast, 1990, p.54). Students’ perceptions of their ability and their involvement in physical education are interconnected. Therefore, it is essential that teachers create and implement lessons that provide opportunities for student success that results in maximum participation. As Aicinena (1991) indicated in his review, “If indeed teachers can affect student attitudes positively, great things can occur in our profession” (p.32).

Pangrazi et al. (1999) provided a study that summarized some of the key components of any physical education program. Their paper concluded that physical education programs should emphasize positive attitudes, feelings of competence, enjoyment in physical activity, and self-management skills because these factors lead to lifetime physical activity.

Physical education courses that are successful in generating lasting, positive attitudes toward physical activity may exhibit certain similar characteristics. In fact, at the secondary level physical education has often been misunderstood by students. Some students respond negatively when running laps and exercise are used as a form of punishment (Pangrazi & Darst, 1991). Students may see physical education as a time for playing some type of sport on a daily basis with little or no structured teaching or learning taking place. Such perceptions often lead many high school students to view physical education classes as a subject reserved only for athletic elites. It is unfortunate that these images of a secondary school physical education class exist in today’s society. However, many secondary schools dispel these perceptions and provide physical education programs that create a positive, exciting experience for students (Pangrazi & Darst, 1991). Physical education can be viewed as a subject that increases knowledge and also affects attitudes and behaviors that promote physical activities.

As a physical educator, the hope is to instill attitudes in students that will motivate them to make physical activities an important part of their lifestyle. Pangrazi & Darst (1991) stated, “An important goal of a secondary school physical education program should be to help students incorporate physical activity into their lifestyles” (p. 3). This is especially important at the high school level because learners are at the age when they begin to make personal decisions about what they enjoy. The decisions they make are usually irreversible and could last a lifetime.

This presents a great challenge for physical education programs that focus on the adolescent learner. Not only is this age group starting to make important life choices, but they are also at an age when they are sensitive to the many barriers that may negatively affect their attitudes toward physical education. Aicinena (1991) reported that a sample exclusively of high school males indicated unfavorable attitudes toward physical education because large class sizes and crowded conditions were bothersome. As a result, many teenage boys may decide to discontinue their involvement in physical activities while in secondary school.

Thus, it is important to offer secondary school students a physical education program that minimizes the chances of creating negative attitudes toward physical activities. Even as early as Grade 9, certain factors will determine whether or not a pupil will continue participating in physical activities. In a study of Grade 9 students, Allison, Dwyer and Makin (1999) found that “self-efficacy (the degree of confidence one has in being able to perform a behavior) … is predictive of physical activity participation” (p. 12). Providing an atmosphere that promotes a high degree of self-efficacy would create positive, lasting attitudes toward physical education. If this can be accomplished when adolescents begin secondary school, it sets the stage for fostering an even greater appreciation for physical activities throughout their high school years and into adulthood.

METHODOLOGY

This chapter explains how the research question was investigated and why particular methods and techniques were employed. A description of the context of the study is given first. This is followed by details of the research participants and the nature of the program. Ethical considerations are presented next. Also included in this section is information regarding the data collection process, and how data was analyzed. Lastly, the topic of verification of the findings is described.

This study took place in an urban Catholic secondary school with an approximate enrollment of 1300 students. It is located in a southwestern Ontario city. The majority of pupils come from middle to upper class socio-economic backgrounds. A small percentage of students come from farming communities.

The study took place in the Grade 9 physical education course. The course is comprised of units lasting approximately two and a half weeks each (the school runs on a semester system) with once a week “fitness” days mixed into these units. Each unit involves physical activities and skill development related to a specific game or sport. Fitness days engage students in fitness activities not related to the specific units. They often include activities such as weight lifting, running, and stationary exercises (sit-ups, push-ups etc.). These days also offer opportunities for pupils to play active sports they normally do not get the chance to do in the course such as wrestling.

I analyzed my own changes in planning and teaching while working with a class of Grade 9 boys, aged 13 to 15 years, during the following two ten -class units of the physical education course:

- low organizational games (LOG) unit; and

- badminton unit.

These two units were chosen over other units because they occurred at a point in the semester when I could devote ample time to record and analyze data.

The purpose of this action research was to investigate and improve my own teaching practice (McNiff, Lomax, & Whitehead, 1996; McNiff, 1998). Thus, I was the subject of my own research. Other participants in the study were the 33 Grade 9 boys in the physical education class. I borrowed this particular class from a colleague for approximately 5 weeks in order to perform the proposed research.

A fellow teacher also participated in the research. In order to help analyze the data and validate my findings, this colleague served as a critical friend (McNiff, Lomax & Whitehead, 1996 ). He is referred to under the pseudonym “John” in this research paper. John is a colleague I trust to work with me in a supportive way and someone who shares my values about the importance of student participation and enjoyment. As a critical friend, John observed my teaching, provided feedback, and reviewed my data, findings, and conclusions. He visited the gym during every lesson as I taught and recorded what he saw in the class. Throughout the research, we compared notes and worked collaboratively to plan and re-plan the lessons. In some classes, we also team taught, each of us taking half the students and teaching separate lessons.

The classes were held in the high school gymnasium, fitness room, weight room, indoor track and school yard. The materials required were those supplied by the school and needed to enhance my instruction. Specifically, the equipment that was used during the LOG unit included foam dodge balls, nets, pylons, indoor soccer balls, basketballs, floor mats, hockey sticks, and tennis balls. The majority of this unit took place in half the high school gym (a moving cloth wall divides the gym into two areas, each the size of a typical elementary school gym). One of the classes for this unit was held outside, in the school yard, using the basketball court and bus area.

The majority of my instruction occurred from 10:44 a.m. to 11:59 a.m. , during the third period of the day. Table 1 provides specific dates, times and key activities for each class of the LOG unit. An ongoing focus of the Grade 9 course is fitness and, as a result, four of the twenty lessons occurred in the school’s weight room and/or fitness room. The two rooms are adjacent to each other. The weight room contains several free weights and machines while the fitness room is an open space with a large floor mat that covers the entire floor.

I used a variety of teaching strategies during the two units. Some of these included organizing class members according to ability level, implementing skill-specific drills, running tournaments, and providing “real” game situations.

Table 1

Details of Low Organizational Games Unit

| Date (2002) | Time | Key Activities Conducted |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1 – November 13th | 10:44 a.m. to 11:59 a.m. | -different varieties of dodge ball |

| Day 2 – November 14th | 10:44 a.m. to 11:59 a.m. | -continued with dodge ball |

| Day 3 – November 15th | 10:44 a.m. to 11:59 a.m. | -personal workout in weight room |

| Day 4 – November 18th | 10:44 a.m. to 11:59 a.m. | -walked laps on indoor track -whole class involved in indoor baseball |

| Day 5 – November 19th | 10:44 a.m. to 11:59 a.m. | -European handball with pylons as nets |

| Day 6 – November 20th | 10:44 a.m. to 11:59 a.m. | -outdoor basketball and street hockey |

| Day 7 – November 21st | 10:44 a.m. to 11:59 a.m. | -indoor basketball |

| Day 8 – November 22nd | 10:44 a.m. to 11:59 a.m. | -team teaching, high intensity warm up in fitness room followed by running indoor track and personal time in weight room |

| Day 9 – November 25th | 10:44 a.m. to 11:59 a.m. | -high intensity warm up in gym followed by indoor soccer |

| Day 10 – November 26th | 10:44 a.m. to 11:59 a.m. | -performed beep test, half the class at a time, followed by sit-ups and push-ups in fitness room |

The materials required for the badminton unit included poles, nets, pylons, racquets, and shuttles. The majority of this unit took place in the entire space of the high school gym. Table 2 provides specific dates, times, and key activities for each class of the badminton unit.

Table 2

Details of Badminton Unit

| Date (2002) | Time | Key Activities Conducted |

|---|---|---|

| Day 11 – November 28th | 10:44 a.m. to 11:59 a.m. | -warm up of sprinting and push ups, modeled basic stance and positioning, free badminton play |

| Day 12 – November 29th | 10:44 a.m. to 11:59 a.m. | -5 laps around indoor track, personal routine in weight room |

| Day 13 – December 2nd | 12:04 p.m. to 1:19 p.m. | -badminton related warm-up, drills involving underhand clear |

| Day 14 – December 3rd | 12:04 p.m. to 1:19 p.m. | -relays for warm up, drills involving overhead clear, game play |

| Day 15 – December 4th | 12:04 p.m. to 1:19 p.m. | -badminton related warm up, modeled and discussed variety of skills and rules, game play |

| Day 16 – December 5th | 10:44 a.m. to 11:59 a.m. | -team teaching, half students performed fitness related activities in weight room while others played badminton games in half gym, students switched activities half way through class |

| Day 17 – December 9th | 10:44 a.m. to 11:59 a.m. | -badminton related warm-up, student demonstration of drop shot, game play |

| Day 18 – December 10th | 10:44 a.m. to 11:59 a.m. | -began doubles badminton tournament, teams set by randomly drawing names |

| Day 19 – December 12th | 10:44 a.m. to 11:59 a.m. | -continued doubles badminton tournament |

| Day 20 – December 13th | 10:44 a.m. to 11:59 a.m. | - written test, badminton game play in half gym, fitness activities in weight room |

The data collected was the kind any teacher might collect as part of his/her responsibility to ensure quality instruction and to assess student learning. However, the results of this study resulted in a research report for academic credit and, for this reason, an ethical review was required. Before beginning the research, I applied to Nipissing University ’s Ethical Review Committee for approval to conduct the study (see Appendix D). The committee approved the research on November 6, 2002 (see Appendix E). I also sent a letter to the district school board administration (see Appendix A) seeking permission to conduct the study. The school board superintendent granted approval.

The project and its expectations were described before the start of the first class in which data collection took place. Students were given an information/consent form (see Appendix B) to take home to their parents. Students returned the consent forms before data collection began. All parents gave permission for their children to participate in the study.

Participants were permitted to withdraw from the study (in terms of providing the response sheets) at any time without prejudice or penalty. Pseudonyms were used in the written research report to protect the identity of the students.

The data from the students were kept in strictest confidence. It was used only for the purpose of the research study and was kept in locked files. Data from and pertaining to students will be destroyed by shredding six months after the project is completed and approved by the university. I will retain my own lesson plans and reflections about my teaching for my own future use .

During the two units, I collected data about student participation by keeping track of attendance and noting the level of participation and student response in the classes. After each class, I gave each student in attendance a form and asked him to:

- record his level of enjoyment of the class on a scale of one to ten (one meaning he experienced a very low level of enjoyment and ten meaning he enjoyed the class immensely);

- indicate why he enjoyed/did not enjoy the class;

- provide reasons if he did not participate.

In addition, at the beginning and the end of the study, I asked the students to complete similar response forms about their enjoyment and participation in physical education and how it may have changed during the two units. Students handed in the completed forms anonymously.

The majority of the qualitative data consisted of my own lesson plans, observations and reflections on my own teaching, and notes on my critical friend’s observations of my teaching. Observations and reflections were collected using two methods:

- keeping a daily journal; and

- speaking into an audio recorder immediately following each lesson.

Written observations were performed first, followed by a more in depth, verbal description of what occurred during each lesson.

The data were analyzed both informally and formally (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Informal data analysis occurred on a continuous basis during the term that the data was collected. As notes were written and experiences taped on the audiocassette, I reviewed the accumulating data to identify and record potential patterns and connections. This information was analyzed on a daily basis to help link students’ level of participation and enjoyment with the activities and methods of instruction I was using at that time. These findings were held loosely but formed the beginnings of the formal data analysis process that followed.

Formal data analysis began after the data collection was completed. Quantitative data was tabled and compared (Miles and Hubermann, 1994). Qualitative data was analyzed through coding and display, summarization, and the writing of memos.

Miles and Huberman (1994) describe codes as “tags or labels for assigning units of meaning to the descriptive or inferential information compiled during a study” (p. 56). Coding involved sorting through data and attaching short words or phrases to data that were related in some way. It was an effective strategy in finding relationships within the written material by categorizing the material in various ways. However, coding became a very tedious and overwhelming task that did not necessarily condense information to bring about significant findings. For this reason, memos were used to compliment codes. A memo is simply a write-up of ideas about codes, definitions of the codes, and connections among codes as they strike the researcher while coding (Miles & Huberman, 1994, p. 72). Memos were a sentence, a paragraph, or even a few pages. They were conceptual in intent in that they bound together different pieces of data into a recognizable cluster to show a general theme. After reading through all the generated notes a number of times, I found that themes kept repeating themselves. It is these themes that are explored under the sub-headings in Chapter 4.

Verification of the findings is an important consideration in action research. Since I, the data collector, was also the subject in this study, I needed a mechanism to test findings and confirm that my findings had some validity beyond my own perception. “Triangulation”, which uses multiple sources of data to confirm findings, was used to address this issue (Miles and Hubermann, 1994).

Triangulation in it’s basic sense “is supposed to support a finding by showing that independent measures of it agree with it, or at least do not contradict it” (Miles & Huberman, 1994, p. 266). There are a number of different ways triangulation can work. For the purpose of this research, it involved my colleague John, the Grade 9 students, and myself as the corners of the triangle. My observations and reflections were shared and challenged by John and the students.

FINDINGS

This chapter presents the findings of the study. It is subdivided into two major sections and focuses on my growth as a teacher and relationships between what occurred during a class and student enjoyment and participation. The first major section presents findings from the quantitative data, which include students’ enjoyment and participation rankings and teacher enjoyment rankings. The second major section describes the findings from the qualitative data including information from student comments on questionnaires and my written and audio-recorded observations.

Findings from the Quantitative Data

Analysis of the quantitative data began to reveal connections between what occurred in a particular class and the level of student and teacher enjoyment of that class. It also demonstrated the inter-relationship between student participation and student enjoyment in physical education that is reported in the literature (George P. Vanier School, 1999).

Relationships Between Class Content and Student Enjoyment

The findings in this section demonstrate a connection between what occurred in a particular class and the level of student enjoyment of that class. The most enjoyed class and the least enjoyed class are revealed as well as what occurred on those specific days. Also, the relationship between student and teacher enjoyment is discussed and the different rankings of pupil enjoyment at the beginning of the research and the end.

Table 3

Average Daily Results of Student and Teacher Class Enjoyment

| Day | Students’ Ranking (out of 10) | Teacher’s Ranking (out of 10) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8.44 |

8 |

| 2 | 7.82 |

7 |

| 3 | 7.90 |

7.5 |

| 4 | 6.98 |

6 |

| 5 | 8.35 |

6 |

| 6 | 7.82 |

7 |

| 7 | 6.68 |

5 |

| 8 | 8.17 |

8 |

| 9 | 7.21 |

7 |

| 10 | 5.32 |

6 |

| 11 | 9.10 |

7.5 |

| 12 | 8.00 |

6.5 |

| 13 | 7.91 |

7 |

| 14 | 8.00 |

6.5 |

| 15 | 8.56 |

8.5 |

| 16 | 9.42 |

9 |

| 17 | 9.00 |

8.5 |

| 18 | 8.36 |

9 |

| 19 | 9.37 |

9.5 |

| 20 | 8.53 |

9.5 |

Table 3 compares student and teacher enjoyment rankings on a class by class basis. Perhaps the most striking result revealed by Table 3 occurred on Day 10 of the research. This particular day was unquestionably the least enjoyed class out of the twenty days that the data were collected. There are several reasons why students may have rated this lesson so low on the enjoyment scale.

The activities for the class on Day 10 were unlike most of the other classes that were researched. During the course of the semester, there are three short periods of time that are dedicated to fitness testing – the beginning, middle and end of the term. This involves pupils attempting different athletic events where their personal results are compared against a standard. Twenty per cent of their final grade is tabulated from how well they perform on these sets of tests. The decision to evaluate and test students in this manner is that of the physical education department of this specific school, so all Grade 9 students must undergo this type of fitness testing and all Grade 9 teachers encompass this exercise as part of their instruction.

Testing on Day 10 consisted of a beep test in which participants continued running at a minimum pace for as long as possible. In this fitness test, students must run the width of the gym before a pre-recorded beep sounds. If they are unable to reach the opposite side of the gym before the sound of the beep on two consecutive attempts they are eliminated and given a corresponding level rating. As the test progresses the time between beep sounds shortens. The longer an individual fails to be eliminated the higher their score. The beep test was conducted twice during this class with half the students running each time. It took approximately fifteen minutes per beep test. Afterwards, all members of the class proceeded to the school’s fitness room where further testing was conducted. This entailed pupils attempting the greatest number of sit-ups and push-ups they could complete in one minute. This was also conducted with half the class performing each time. All individual results were recorded by a partner in their course journals, which were collected at the end of the period (Journal, November 26, 2002 ).

My instruction time was spent reminding students how the testing worked, ensuring they were honest with their results, encouraging them to work hard and give their best effort, and monitoring any improper behavior (Tape Recorded Comments, November 26, 2002). John was also present during the class and offered the same type of instruction. In fact, since he was already familiar with the procedures of the fitness testing, he did the majority of the explaining to students (Journal, November 26, 2002 ).

While Day 10 proved to be the least enjoyed class for these Grade 9 students, Table 3 also indicates that Day 16 was the class most enjoyed by pupils. This day was also unique in that it differed from the usual structure and content of the majority of the lessons. In this particular period, John and I decided to take a team teaching approach where each of us took half the students and ran our own different activities (Journal, December 5, 2002 ). Half way through the class we switched groups so that every student had the opportunity to experience both of our lessons. I continued with the Badminton unit using half the gym, while John took pupils to the wrestling room to perform wrestling activities (Journal, December 5, 2002 ). The opportunity for two teachers to teach one class is very rare, but, since John and I were in the unique position to do so, we thought we would see how it would affect student enjoyment. Before the class had begun, we had hypothesized that most, if not all, students would react positively to this format and type of teaching (Tape Recorded Comments, December 5, 2002 ).

Some of the reasons we thought students really enjoyed this class were:

- they had the opportunity to participate in two very different activities - even if some students only enjoyed one of the two sports they still played it for half the class;

- two smaller groups have less potential for young people to misbehave then when they are in one very large group; and

- two thirty -minutes lessons on two very different sports were easier to pay attention to then one sixty-minute lesson on the same sport (Tape Recorded Comments, December 5, 2002 ).

We also thought that, if the activities were presented in a relaxed, non-competitive fashion, some of the less athletic students would feel more comfortable participating with their peers (Tape Recorded Comments, December 5, 2002 ).

The third significant finding revealed from Table 3 is the relationship that appears to exist between student and teacher enjoyment. In seventy-five per cent of the cases, the difference between enjoyment ratings between students and teacher was less than one. Only one class existed where the difference was greater than two. This demonstrates that, when the students were having fun, usually so was the teacher and vice versa.

Table 4

Beginning and End Results of Student Enjoyment

Day |

Students' Enjoyment Ranking (out ot 10) |

|---|---|

1 |

7.89 |

20 |

8.97 |

Table 4 compares student enjoyment rankings at the beginning and at the end of the research. It shows that this particular group of Grade 9 students began the research session with an already established enjoyment of physical education. It also reveals that, by the end of the two units, the overall enjoyment of class members increased by slightly more than 1 point.

Student Participation and Student Enjoyment

The findings in this section support the assumption that participation and enjoyment go hand in hand (George P. Vanier School, 1999) and that students are likely not to enjoy physical education if they do not participate.

Table 5

Beginning and End Results Comparing Student Enjoyment and Participation

| Day | Students' Enjoyment Ranking (out ot 10) |

Students' Participation Ranking (out of 10) |

|---|---|---|

1 |

7.89 |

8.76 |

20 |

8.97 |

9.38 |

Table 5 compares the student enjoyment and participation rankings at the beginning and the end of the research. As revealed in the previous section, the student enjoyment ranking at the end of the research was higher than at the start. Table 5 shows that the same can also be said of student participation. While the increase in participation ranking was not as great as the increase in enjoyment, the data supports the conclusion that there was an inter-relationship between student participation and student enjoyment

Other data from this research showed that individuals who did not participate ranked their level of enjoyment very low. In fact, the highest enjoyment ranking from a person who did not participate was a five with the majority of non-participating students submitting a rating of one (Student Response Sheet, November 18, 2002 ). It should also be mentioned that only one of the individuals who did not participate in a class did so of his own free will (Student Response Sheet, November 21, 2002 ). All of the other students who did not participate did so because they had forgotten their gym clothes on a particular day’s lesson and, therefore, were not permitted to take part in the physical activities. After circling an enjoyment ranking of one on their daily questionnaire, beneath the question, “If you did not participate today, please state why,” the majority of students explained, “I forgot my gym clothes,” or, “I was out of uniform today” (Various Student Response Sheets, November 13 to December 13, 2002). The student who chose not to participate did so on Day 7 and answered, “No; because of basketball tonight I did not want to injure myself” (Student Response Sheet, November 21, 2002 ). The only other reason given for non-participation (where the students watched from a bench and did not change into gym clothes) was injury such as a pulled muscle (Student Response Sheet, November 26, 2002) or the wearing of a cast on one arm (Student Response Sheet, December 13, 2002).

Findings from the Qualitative Data

Analysis of the qualitative data explored my use of the action research cycle to improve my practice and revealed in greater detail connections between course content and student participation and enjoyment. The section begins by describing what I learned about planning and implementation related to Hopper’s (1996) action research process - planning, acting, observing, reflecting and re-planning. Then the section identifies specific teaching strategies that impacted on student participation and enjoyment.

Changes in My Planning and Implementation Practices

As mentioned in Chapter 1, action research involves a cyclical pattern of planning, acting, observing, reflecting and re-planning (Hopper, 1996). My action research comprised repetitions of this cycle. This section investigates some of my experiences in each of the 5 phases of the action research process and how they contributed to improving my own professional teaching practice so that students increasingly enjoyed lessons as the research period progressed. The findings presented in this section demonstrate how the action research process occurred in a cyclical manner. Figure 2 illustrates a summary of the findings related to Hopper’s phases of action research. This illustration is presented with Hopper’s five phases as the inner slices of a pie chart and the key findings from this study connected to the outer slices. It is presented in this fashion to convey how each phase depends on the previous phase in a cyclical fashion and how each set of findings were generated from the findings of the previous phase.

Figure 2

A Summary of Findings Related to Hopper's Phases of Action Research

The first phase of the action research process, planning, was conducted on a long-term basis. That is to say that a group of lessons was planned well in advance of implementation. For example, the entire first week’s lessons for the initial unit, LOG, were designed before the first class took place. The ideas for lessons were produced from my past experiences teaching these units and this particular age group. The equipment and facilities that would be available during a specific lesson were also considered in the initial planning. Lessons were also created with a certain level of flexibility to allow students some say in what we would be doing on a particular day. Also, there was a need to have back-up lessons in place because, in some instances, the environment would change, for example from a gymnasium setting to a weight room or outdoor facility (Journal, November 13 – 19, 2002 ).

My experiences during the research led me to conclude that, while long-range planning of an entire unit, before the first lesson even begins is helpful in visualizing the overall goals, it is not a substitute for daily planning. The original long-range plans were changed so drastically during the course of each of the units that it felt almost a “waste of time to have created them so far in advance” (Tape Recorded Comments, November 18, 2002 ). My preliminary planning for the LOG unit involved students in a different game each day until the final two lessons. Then I was going to allow students the freedom to choose their favorite activities from among the ones they experienced. This is definitely not how things turned out. As I became more responsive to students to improve each successive lesson, the students repeated some activities on consecutive days, played more than one activity during a lesson, and could not come to a consensus on their two favorite activities during the final classes of the unit (Journal, November 13 – 26, 2002 ).

The second phase of the action research process is simply acting on the plan that I had created. The question therefore becomes, “Did I in fact act out the lesson that was planned?” The answer for the most part was, “Yes.” The activities that were specifically planned for each of the lessons were carried out approximately 75% of the time. Examples where lessons were carried precisely as they were intended included classes 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 17 (Journal, November 13, 14, 18, 20, 22, 25, 26, 28, December 9, 2002). In the other 25% of the cases, I added in more drills that the students seemed to be enjoying, or left out an exercise because the flow of the class perhaps was not going well and I thought a change in pace was necessary to keep pupils interested. In two classes during the badminton unit, the drills and activities were altered because we were only given half the gym instead of the entire facility as is customary with this unit (Journal, December 5, 13, 2002). In both cases, this change occurred at the last minute, just before class was to begin. In one instance, I was told the class could not use the gym at all and I had to resort to the weight room to conduct the lesson. The planning for this class, Day 12, was not acted upon at all and I created activities for students on the spot. For most of the period, the participants were given free time to work out as they pleased on the exercise equipment (Journal, November 29, 2002 ).

Part of the reason for students’ improved enjoyment was acting on certain planned activities while not acting on other exercises. In other words, I became a better judge of determining what parts of the lesson to act upon and what parts to leave out in order to increase student enjoyment. Day 14 was a good example as I shortened the planned length for certain skill development drills and increased the time to practice these same skills in a game situation (Tape Recorded Comments, December 3, 2002 ).

It is interesting that, as the level of enjoyment for each class increased, the number of lessons that were specifically acted upon decreased. The audiotapes of my research reveal that this was not because of poor planning. In fact, as I became more knowledgeable of what the students enjoyed, my planning improved and I was able to act out more (but not all) of my planned work. This became apparent by Day 15 when my planning incorporated much more individual feedback and game play and far less Socratic modeling and group drills (Tape Recorded Comments, December 4, 2002 ).

The third phase of action research, observing while the plan was being acted upon, also improved as the research period progressed. During the first 10 lessons, the number of written observations was dramatically higher than during the final 10 classes. This was mainly due to “learning the names of several of the students while trying to determine their learning needs” (Tape Recorded Comments, November 15, 2002 ).

As expected, some students needed greater attention than others did, and I had to observe them more closely then some of the other participants. I also needed to observe closely how I reacted to these and other pupils in order to determine what was effective in improving their enjoyment and also the enjoyment of the class as a whole. The best example of this occurred during the first two lessons when, after the first class, one student complained to John and other members of his educational support team that he was being picked on by other students while playing dodge ball (Journal, November 13, 14, 2002). He mentioned that some participants were intentionally throwing the ball at him. I did not notice this on the first day, so when John pointed this particular pupil out to me at the beginning of the second day, I paid close attention to him and the youngsters around him to see if there was any inappropriate behavior that I could observe. These observations allowed me to identify students that I would need to watch closely and deal with frequently, especially during the first few classes (Journal, November 14, 2002 ). As I became more familiar with them, I was better able to predict how they would act in certain situations and how to effectively handle their actions. Similarly, through observations, I was able to “grasp a better feel for what worked well in class” (Tape Recorded Comments, November 28, 2002 ). Because student behavior and enjoyment improved, especially during the last quarter of the research, I found I did not need to observe as much. This was not due to a decreased need to observe, as the potential for decreased student enjoyment can occur at any time; however, I believe I was a more focused observer since I now knew better what was important to observe (Tape Recorded Comments, December 4, 2002 ).

The fourth phase of action research involved two types of reflecting sessions. In one, I took a few moments after each lesson to reflect on what worked well and what could be improved and wrote these thoughts in my journal. I then expanded on these personal thoughts and verbalized them on an audio recorder. The second type of reflecting session involved debriefing between John, who was my critical friend (McNiff, Lomax & Whitehead, 1996) and myself. The content of these sessions was also noted on audiotapes and paper. While these sessions took the least amount of time of the five phases, I found them to be the most valuable in enhancing my teaching practice.

I was not surprised to discover that the issues I identified in my own reflection sessions were often analogous to the issues John brought up in our debriefing sessions. This is in part due to the similar values we share as professional teachers and our common ideology as to what we feel is important to emphasize and establish in a physical education class. I was surprised however at the significance of having a second observer in the classroom and how valuable a tool he really was. Despite sharing the same overall view of what was happening in each class, the fact that I was hearing it from a trusted colleague made the content much more significant. Also, John was excellent in voicing the strength of a particular lesson and all his concerns in a straightforward manner.

There were some issues that arose in our debriefing sessions that I thought were minor. However, John made me realize that they were important and needed to be dealt with immediately. A good example of this took place during a debriefing session after the seventh day when student behavior appeared to start getting out of hand. John made the comment to me that “you expect them (the students) to be nice like you… they need to be watched carefully and be held accountable for their actions” (Tape Recorded Comments, November 28, 2002 ). While this may have been difficult for me to hear initially, it was exactly what I needed to hear. His comment motivated me to deal with student behavior more seriously and realize a potential weakness in my teaching approach that perhaps has always been there, but has been invisible to me. We both agreed that this issue of behavior management had a large impact on student enjoyment and participation (Tape Recorded Comments, November 28, 2002 ).

Debriefing also helped me establish new ways of forming small groups within the class. Through John’s guidance and suggestions, I learned new methods of separating students into teams that I had never used in previous classes (Journal, November 28, 2002 ). I also implemented a new routine at the start of each class for taking attendance and beginning a warm-up (Journal, November 29, 2002 ). John’s input and my own reflections created an outstanding basis for the fifth and final stage of the action research process, re-planning.

The fifth phase, re-planning, completed the action research cycle and set the stage for the next one. It was a result of the work that transpired over the first four phases and, in most cases, created a revised or new plan based on new concerns. It was intriguing to notice that in the end, the time spent planning was almost equivalent to the time re-planning. This was especially the case during the first half of the research process when I was attempting to establish a feel for the group and come up with different, effective teaching strategies and activities that the students would enjoy. After the first few days of the LOG unit, I noticed that if we were playing a game that some of the participants did not enjoy, it was useful to change to a different game half way through the period to increase their enjoyment (Journal, November 20, 2002 ). While the original plan was to play one game, the re-planned lesson included two games during the same period (Journal, November 20, 2002 ).

Plans were also altered as a result of a change in facilities such as only having access to half the gym or losing gym space entirely (Journal, November 22, 29, December 5, 20, 2002). The warm-ups at the beginning of the research looked much different as the days continued. Warm-ups became more complex and increased in physical intensity (Journal, November 22, 25, 28, 2002). Introductions to new skills changed form longer periods of time where students sat and listened to shorter time frames and more time for actual play (Tape Recorded Comments, December 4, 2002 ). Because of the large size of the class, games during the LOG unit such as indoor soccer, basketball, and European handball were re-planned with shorter shifts (Journal, November 19, 21, 25, 2002). This meant that the students who were sitting off had to be more attentive to what was happening while others were playing so they would not miss their turn to play.

In a couple of instances, lessons were completely re-planned as a result of a reflection session. John and I felt that it would be beneficial for the class if he led the instruction on some occasions (Journal, November 26, 28, 2002). That way he could demonstrate to me some methods of instruction he had found to be very successful in the past. It offered me the opportunity to see first hand teaching strategies we had discussed in our reflection sessions and to view pupil behavior while instruction was being conducted. These specific, re-planned lessons had a very positive effect on student enjoyment as participants ranked them very high on their class questionnaires (see Table 3, Days 8, 11 and 16).

Changes in Teaching Strategies

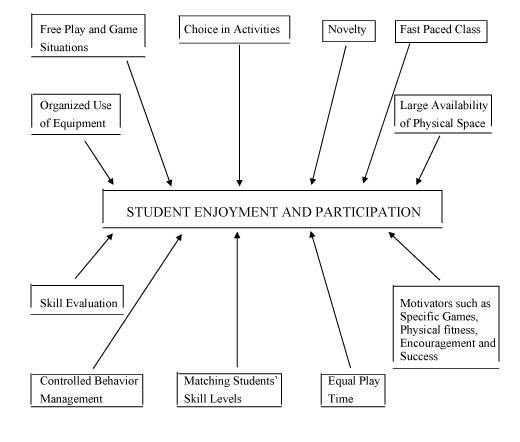

This section describes my learning about specific teaching strategies that affected student participation and enjoyment. It provides greater detail then the previous sections about the manner of instruction and what students enjoyed and did not enjoy. The term teaching strategies is used broadly here to refer to practices relating to instruction, evaluation, and classroom management. There is discussion of free play and game situations, providing choice and novelty in activities, pace of classes, matching students’ skill levels, and equal play time. The impact of teaching on pupil motivation is addressed. There is also discussion of evaluation and behaviour management practices and ways of dealing with equipment and physical space. Figure 3 illustrates a summary of factors that contributed to student participation and enjoyment. The findings are represented in the form of a mind map to convey the idea that all of these factors had an affect on student enjoyment and participation in their own ways. One finding did not hold greater significance than another. While some of the findings may have had a different impact on individual students, all of them were considered important discoveries concerning my teaching practice.

Figure 3

A Summary of Factors that Contributed to Student Participation and Enjoyment

The most enjoyed activities by students in this Grade 9 group involved free play and games. Free play involved the opportunity for pupils to work out at their own pace in the weight room and to select the machines and free weights they desired on that particular day (Journal, November 15, 22, 29, 2002). They had experienced all the machines and equipment in this facility during previous lessons and were familiar with the safety rules and proper etiquette. Several students commented on their questionnaires that they liked this type of freedom. Some of the statements included the following:

“I enjoyed it because you let us use the machines we wanted and we got to work out” (Student Response Sheet, November 14, 2002 ),

“The freedom to work out at your own pace, time, and level” (Student Response Sheet, November 14, 2002 ); and

“Enjoyed the weight room and the freedom to work out at your own pace” (Student Response Sheet, November 29, 2002 ).

Games refer to students playing in a “real game” as opposed to performing drills or listening to the instructor describe proper technique. The LOG unit allowed participants to perform a short warm-up and go directly into a game or sport related activity (Journal, November 13, 14, 18, 19 20, 21, 25, 2002). There were no drills during any of the lessons for the ten classes in this unit. Observations and verbal student feedback revealed that the majority of this group of teenage boys took pleasure in playing sports such as floor hockey, indoor soccer, dodge ball, basketball and European handball without discussing the specific skills required to play these games well (Tape Recorded Comments, November 13, 19, 20, 21, 25).

This tendency to want to play the game became even more evident during the badminton unit when many students explained that they greatly enjoyed the tournament portion of the unit. The tournament involved a class design where, once all students arrived, we quickly made up teams and played timed games (Journal, December 9, 10, 12, 13, 2002). Scores were recorded and teams were assigned different courts where they would compete against other teams on an ongoing basis during the period. The tournament platform continued from Days 16 to 20. Remarks such as, “The tournament was very fun,” and, “I enjoyed the tournament style of today and the free badminton play,” were common feelings expressed by participants (Student Response Sheets, December 12, 2002 ). After ranking one of the lessons a perfect ten on the enjoyment scale, one student wrote that it was “because we got to play games instead of drills” (Student Response Sheet, December 4, 2002 ).

Interestingly, the majority of pupils enjoyed the tournament regardless of their partners. To organize the teams on the first day of the tournament, I drew names out of a hat (Journal, December 5, 2002 ). John and I felt this would be the fairest way for all students. On subsequent days, if a player’s teammate from the previous day was absent, I would randomly assign him a new partner from those that did not have one. Through the four days of the tournament, only one student on one of the days complained that the “tournament sucks” because he felt he was partnered with a classmate who was a weak badminton player (Student Response Sheet, December 12, 2002 ). This was definitely a unique situation since the overwhelming bulk of observations and student remarks supported the structure of the tournament style of play (Tape Recorded Comments, December 10, 2002 ).

The Grade 9 students enjoyed having a say in what took place during the lessons. This was clear at the start of the research and obvious during the LOG unit when participants voted for the sport of their choice. I gave them three sports to choose from and they voted for their favorite (Journal, November 13, 14, 18, 20, 21, 2002). The sport with the most votes was the game we played that day. Some students really supported having choices and wrote, “I enjoyed this class because we got to play a fun game and you let us choose the games we wanted to play” (Student Response Sheet, November 13, 2002), and, “I enjoyed the freedom to play the sport I liked and the freedom to play at my own pace” (Student Response Sheet, November 20, 2002). There were no written comments about decision making by pupils during the badminton units but they were given some opportunities to vote on different activities (Journal, December 3, 4, 2002).

Interestingly, the LOG unit also became more enjoyable for participants when two different sports were played instead of one for the entire time of the class. Day 8 consisted of half the period wrestling and the other half working out in the weight room (Journal, November 22, 2002 ). One member of the class rated the class a ten on the enjoyment scale and explained it was “because we got to wrestle and to work out” (Student Response Sheet, November 22, 2002 ). Even those individuals that only liked one of the sports still enjoyed the class when two sports were played. Also rating a ten on the enjoyment scale, a second person remarked, “I enjoyed the strength/wrestling part of the class” (Student Response Sheet, November 22, 2002 ). The two sport lesson also took place during Day 16, the highest student-ranked day, as well as Day 20 (see Table 3). After the final day, a pupil wrote, “I enjoyed this class because we did two activities, badminton and the weight room” (Student Response Sheet, December 13, 2002).

Learners enjoyed small twists to an already familiar game. Day 9 consisted of playing indoor soccer for half the period and then, for the second half, playing the same game with two balls instead of one (Journal, November 25, 2002 ). The effect was that participants tried even harder during the second part of this class and “appeared to be having even more fun then in the regular method of play” (Tape Recorded Comments, November 25, 2002 )

This observation led me to discover that many students also liked playing a new game and learning a new skill (Journal, November 19, 2002 ). The former situation was apparent after Day 5 when most of the class played European handball for the first time. Comments written by participants included “interesting” and, “I enjoyed European handball. I never played it before” (Student Response Sheets, November 19, 2002 ). The latter situation was apparent after Day 13 when a pupil rated the class a 10 on the enjoyment scale and explained, “because I learned a new skill” (Student Response Sheet, December 2, 2002 ). My further insight was that the key to the enjoyment of learning a skill was that it indeed had to be new (Tape Recorded Comments, November 28, 2002 ). Observations made it clear that several badminton players had trouble focusing on instruction when it related to a skill with which they were already familiar. Basic skills such as handgrip, stance, and forehand and backhand clears were of little interest to most of the Grade 9 students. However, drop shots, smashes, and short serves were skills that sparked great interest because many students were unaware these types of shots existed in the game of badminton. Day 15 was a perfect example because this was a rare class in which pupils were seen enjoying drills and listening to information concerning these new skills (Tape Recorded Comments, December 4, 2002 ). In many of the earlier badminton lessons, students were extremely eager to skip the learning of skills and move directly into game play, which usually took place toward the end of the period (Journal, December 3, 2002 ).

For this Grade 9 group, a fast-paced atmosphere was conducive to an enjoyable class. This type of class was organized so that students moved from one activity to another very quickly. As one student wrote after the first lesson, “I enjoyed playing the game without constant interruption” (Student Response Sheet, November 13, 2002 ). By the end of the research period, participants still felt this way as comments included, “We played a lot, no stoppages, lots of time, organized too” (Student Response Sheet, December 12, 2002) and “organized and quick to activities” (Student Response Sheet, December 13, 2002). Day 4 showed the opposite to also be true – that a slow paced lesson was not an enjoyable experience - as a class member stated “not as fast paced,” and rated the day a below average, six out of ten (Student Response Sheet, November 18, 2002).

One method of instruction that provided a fast paced, organized class included arranging teams quickly by simply numbering the students from one to six - for example, if six teams were needed to start a game (Journal, November 21, 25, 2002). Another strategy included saving all paper work for the end of the class after physical activities had ended. This meant combining written tests or self-evaluations with the end of class questionnaires and handing out any required literature such as the rules of badminton at the end of class when students were headed to their knapsacks anyway (Journal, November 26, December 12, 13, 2002). Arranging pupils as they chose a badminton racquet was also helpful in keeping them organized and moving. During Day 11, students were permitted to select a racquet in groups of six, instead of having the entire class of 33 teenagers attack the equipment all at once (Journal, November 28, 2002 ). Each group of six was given seven seconds to choose a racquet and sit down so the next group of six could then do the same. It seemed very simple at the time, but very effective in maintaining a fast paced lesson.

Placing students into smaller groups also proved efficient in other ways. Day 12 involved a lesson in the weight room where the class was divided into groups of ten and each group used the cardiovascular equipment for ten minutes at a time (Journal, November 29, 2002). This made the period seem to go by much more quickly. Grouping allowed me to avoid combinations of youngsters who did not work well together and prevent any misbehavior. When partnering students for the first class of the badminton unit, I had them hit the shuttle back and forth with a classmate of their choice, but had them partner up with the person beside them, not the person they chose to hit with (Journal, November 28, 2002 ). While they felt slightly disappointed (and perhaps even a little deceived) with this method of organizing partners, they still enjoyed the class and how smoothly it flowed (Tape Recorded Comments, November 28, 2002 ).

As a fast paced environment became a desired feature by the class, each lesson of the badminton unit began in a way that promoted this feature. Once people arrived, they were to set up the nets. The first individuals to set up the nets properly were given the freedom to obtain a racquet and begin playing. Those who came later did not have the opportunity to begin playing since the courts filled up rather quickly. Once everyone arrived, I would begin the formal part of the class. This was an “excellent technique in establishing a smooth transition to begin the days activities” (Tape Recorded Comments, December 2, 2002 ).

Matching Students’ Skill Levels

The data revealed that when the class was organized according to ability level the lessons ran smoothly and were more enjoyable for the class as a whole (Journal, November 25, December 4, 13, 2002). The badminton unit ran much more smoothly than the LOG unit partly due to my familiarization with the ability levels of all members of the class (Tape Recorded Comments, December 13, 2002 ). When setting partners during drills and game play, I carefully paired pupils so that they could be competitive as a team. In some cases, one person on the team would help his less-skilled partner. This also made for closer scores when playing games and greater parity among competitors. It was interesting to observe students at the end of the unit when, on the last day of the unit, I allowed them to choose their own partners. The majority of the youngsters chose a partner with similar ability levels, rather then their best friend or the classmate they usually selected as a partner (Journal, December 13, 2002 ). By this point in the unit, everyone in the class knew who the strongest badminton players were, but they organized themselves so that the competition would be equal and so that one team would not dominate the others. This proved to be the preferred form for class competitions and resultantly more enjoyable (Journal, December 13, 2002 ).

Pulling names out of a hat to decide the pairs during the badminton tournament was an exception to my partnering of students and resulted in stronger and weaker teams competing with one another. The parity that existed in many of the preceding badminton classes no longer existed (Tape Recorded Comments, December 5, 2002 ). I was very excited when, the day after the tournament, Day 20, students chose to go back to the more evenly matched organizational method of competition.

For the LOG unit, matching students’ skill levels meant creating teams that were evenly matched so that one team did not dominate another. Even as early as the first day, I had to reorganize teams for dodge ball because the same group of players easily won three consecutive games (Journal, November 13, 2002). As I became more “familiar with the athletic abilities of individuals, making more evenly matched teams became an easier task” (Tape Recorded Comments, November 25, 2002 ).

The LOG unit involved games such as basketball, indoor soccer, and European handball where only two teams of five could play while the others sat out. Consequently, it was important that I organized the games so that everyone received equal playing time (Journal, November 19, 21, 25, 2002). The class played European handball throughout Day 5 and some participants voiced their displeasure at not playing as many shifts as their colleagues (Journal, November 19, 2002 ). During the period, I lost track of which teams had competed and how many shifts each team played (Tape Recorded Comments, November 19, 2002 ). I should have been better organized to ensure the six teams received equal playing time. On Day 9, we played indoor soccer. I organized which teams would play each other in a six team rotation and wrote the schedule down before the class began (Journal, November 25, 2002 ). The students noticed a much more equal system of playing time and enjoyed the class as a result. One youth who rated this class a 9 out of 10 on the enjoyment scale wrote that it was “because everyone got to play at least two games” (Student Response Sheet, November 25, 2002).